Ivan Rogers - essay

Ivan Rogers, Anna, near Carterton, 1982

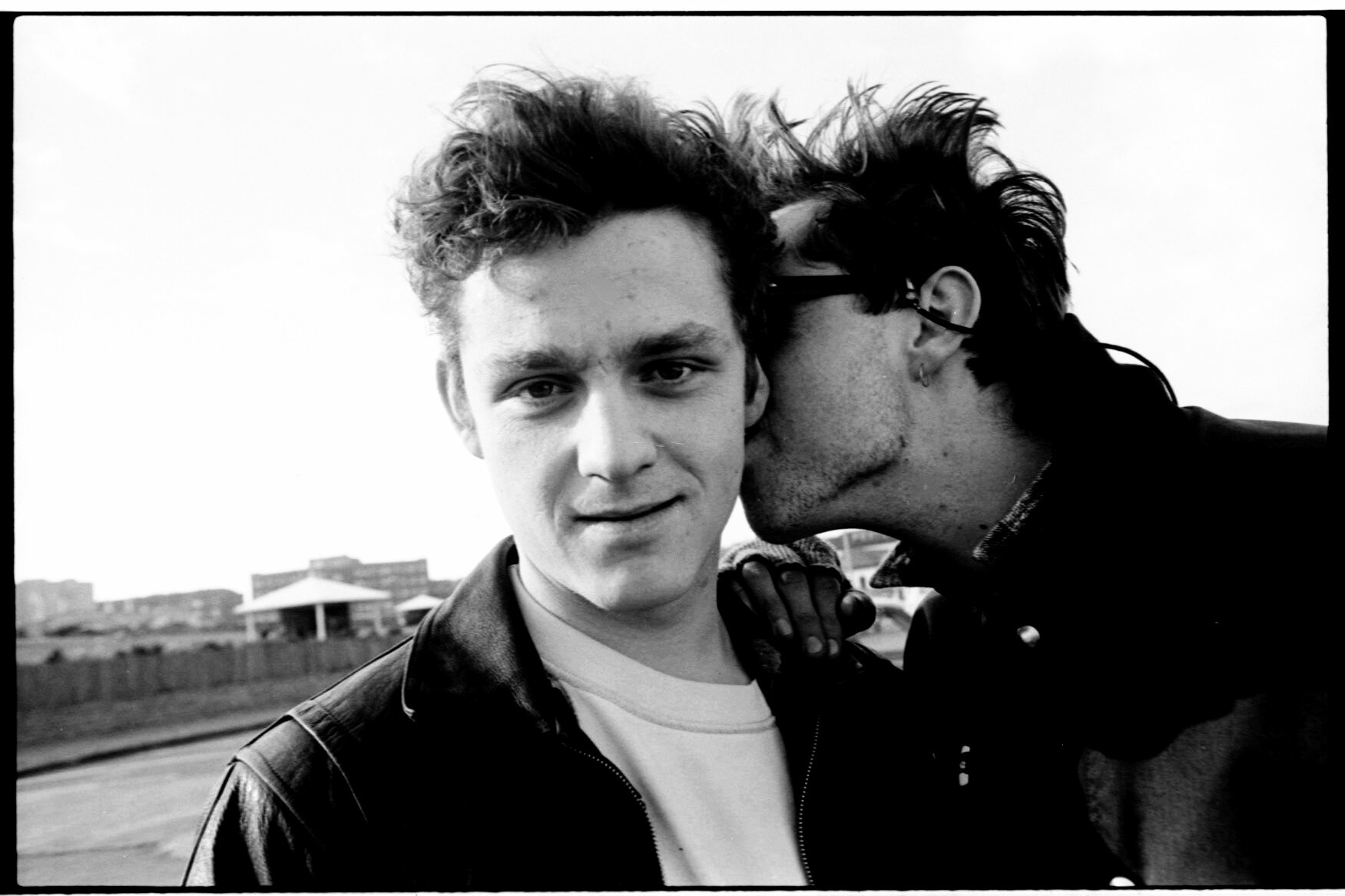

Now, now: Considering the early photography of Ivan Rogers

Essay by Nicholas Graham Haig for PhotoForum

14 May 2020

The Red Tenda of Bologna, John Berger’s dream-like meditation on the ‘improbable beauty’ of the titular Italian city, on memory, art and his relationship with a favourite uncle, opens with the lines: ‘I should begin with how I loved him, in what manner, to what degree, with what kind of incomprehension’ [1].

Meanwhile in his novel The Rings of Saturn, German author W.G. Sebald asked: ‘Across what distances in time do [...] elective affinities and correspondences connect?’ [2]

My concern here is precisely with such affinities, and in particular with the capacity of that which was to create radical transformation in the present. In other words, I’m interested in, firstly, the “revolutionary” potential of these puzzling and often troubling connections and correspondences, and secondly the possibility of redeeming lost or passed-over or abandoned pasts. Or if not redeeming then at the very least looking at anew, for, and as Peter Handke puts it, ‘Who says the world has already been discovered?’ [3]

Ivan Rogers, On the road to Dunedin, 1981

I’d intended to give a full-bodied account of the strange sense of agitated enchantment that took hold of me when considering a series of informal portraits – peopled pictures – Ivan Rogers made in the early 1980s [4]. Instead, and due to a failure to find a language up to the task – up to the task of capturing how I fell in love with these photographs, in what manner, to what degree and with what kind of incomprehension – this essay is a preliminary sketch of what I hope will in time become a more fleshy consideration of his work.

Rogers, who works for the Department of Conservation, lives in woodland south-west of Nelson together with his wife, artist Fi Johnstone, in a home which is part mud-brick barn and part chapel. Born in Christchurch in 1958, he moved to Wellington in the late 70s having “fallen in love” with the city after attending the 1977 student arts festival. The one, he told me, “Where the Scavengers and Suburban Reptiles debuted.”

In 1980 Rogers attended Bill Main’s Wellington Polytechnic photography course, and that same year found him playing bass in Bill Direen’s band Six Impossible Things. Then, in 1981, Rogers worked on a PEP scheme for – and occasionally exhibited with – PhotoForum. From that time on he just “Kept taking photos of friends and situations in Wellington, Christchurch, Auckland and later Sydney.”

Ivan Rogers, Steve, The Terrace, 1981

Rogers’ photographs from this period, a period just before the Fourth Labour Government’s neoliberalisation of the country, now look like relics from a distant age. However, and as Andrew Burke contends, in ‘unguarded moments’ the perception of decay can provoke nostalgia and ‘be transformed into the picturesque’ [5]. And yet, the degraded objects of earlier eras, such as the idiomatic images of Rogers’ friends, lovers and acquaintances, may also hold ‘buried deep within them the utopian desire absent from present things’ [6].

Or as Martin Heidegger once put it: ‘Our worlds, and consequently our meaningful relations to things, are always based in something that can't be explained in terms of the prevailing intelligible structure of the world’ [7]. Could Rogers’ photographs, these image-objects degraded by time if not intention, offer alternate “intelligible” structures of the world?

To put it in more concrete terms, although I had hoped to draw out some of the explicit political and social “affordances” of the early 1980s from these photographs, or at the very least paint a picture of things that I am suggesting should be redeemed, instead I make the claim that that time affords radical promise without any form of contextual substantiation. My question – which I don’t intend to answer here – is this: how might such photographs work to create a rupture with respect to our current political and indeed “temporal” coordinates? Or, plainer still, how might such images help us re-think and hence break with the “landscape” of late (late!) capitalism?

Rogers, who I’ve had the pleasure to know for the last decade or so, allowed me to roam freely through his archives and in the process of sifting, matching, pairing and separating, a particular set or series of images took shape. Although much of his work is characterized by ironic framings and a droll eye, the photographs that most moved me were of more ordinary-intimate moments: that is, of young folk in the commonplace – picnicking, road-tripping, hanging out. What this means is that the black and white photographs which are my subject here, photographs which span the years 1981–1985, are by no means representative of Rogers’ output. Passed over is his quite glorious work documenting bands, graffiti, and the shifting built environment of late 20th century New Zealand.

My final selection was informed by the imprecise rationale of what they may do, and indeed, do to me, now . That is to say, my concern is with questions relating to the possible afterlife or afterlives of the moments in question, with Rogers’ photographs’ potential to be retroactively meaningful – in a profoundly destabilising and, in a certain sense, ecstatic manner – now .

The photographs that feature here are very much of their time and could be read as predictable and almost clichéd documents of New Zealand’s countercultural scene of the 1980s, in that they are low-fi, causal, emplaced, particular, vernacular; simply reportage of the commonplace.

And yet, the commonplace is of course never just that. It is in the commonplace that our lives are mostly led, and this place is homed by weirdos, by people ensnared by inexplicable drives, by unruly and often contradictory desires. That is, by you and me.

However, the way in which Rogers’ encountered and engaged with the day-to-day creatureliness of human being is what I believe sets his work apart. In this way, it is what could be termed the “emotional indexicality” of his photographs that provides radical promise. By this I mean that they may be seen to function as ciphers of a world passed over not just in a material or philosophical sense but in terms of the possibilities for certain types of feeling.

Ivan Rogers, Carolion, Auckland, 1983

Rogers has described the construction of a number of these photographs as involving “using a wide-angle lens in available light in available situations.” Put differently, they are the artfully un-staged snapshots of a photographer seemingly working without founding principle. Or at least that’s how they come across: situational, accidental, incidental. Of course, each image has been sensitively constructed, with the right angle sought out, the slight adjustment made, the parallax shift effected.

There is also typically nothing uncanny in or about these photographs, there is no peculiar tilt to them. They do not tend to defamiliarise or, for the most part, poeticise. Instead, they simply document the day-to-day without great flourish or paying particular attention to the everyday weirdsome (Peter Peryer’s forte) or humdrum sublime (as Wayne Barrar’s early work did). But, and in an understated way which only adds to their enigma, the inexplicability of the other (of one another) is on full display.

Ivan Rogers, Denise, Wellington, 1984

Ignoring the formal qualities of the images, what seems to make these photographs “matter” is the relationship between Rogers and his subjects. These are not images taken on the sly. Instead, Rogers’ seems not to have had subjects but co-conspirators.

And although his accomplices are not always posed this is not to say they are unaware of the camera. They act up, act along, knowing full well the camera is on them. But, again, this acting up by no means implies that they were in control.

Rogers’ photographs can’t be said to represent a particular ‘philosophical attitude’ towards reality. But then the story of a shattered life – that is, any life, every life, to varying degrees – can only be told and apprehended in bits and pieces. What I believe each of these photographs offers, and each in their own way, is a glimpse of the (un)quiet contours and contortions of being. But Rogers’ is not a penetrative gaze. Instead, it is tender, loving even, though that is not to say that it is not distant, anxious or baffled.

A camera, in such circumstances, should be understood as not only an extension of but complicating factor in social life.

What was it that made it possible to take photographs in such a way? And what material and social circumstances enabled the sort of intimacies and emotional idioms which seem to be on display here?

Adam Phillips, in an excellent essay discussing the work of Diane Arbus, contended that her work should be viewed by way of the prism of sociability and, indeed, thwarted sociability. Of course, Rogers work, particularly in terms of methodology, couldn’t be more different from Arbus’. However, it is precisely this tension between proximity and remoteness (and between sociability and the fundamental estrangement of one to another) which lights up Rogers’ photographs from this period.

They are, you could say, distinguished by a beautifully woozy dialectic between intimacy and distance, and suggest a stance towards the other which is receptive to their presence and forgiving of their fundamental and unavoidable absence or “elsewhereness.” However, the stress of the social and the fact of them being creatures with an unconscious is always apparent.

How to resist either luxuriating in their (now quite fantastic) pastness or folding them neatly into the present?

Perhaps what this collection of Rogers’ photographs offers is an opportunity, in our age, for a form of ‘commonplace utopian desire’ to be witnessed. Perhaps that is it. And perhaps that is enough. For now.

Footnotes

[1] Berger, John. The Red Tender of Bologna, (London: Penguin Books, 2007), 1.

[2] Sebald, W. G. The Rings of Saturn, (M. Hulse, Trans.), (London: Vintage Books, 2002), 182.

[3] Peter Handke as cited in Fritzsche, Peter. Stranded in the Present: Modern Times and the Melancholy of History, (Cambridge, Massachusetts, and London, England: Harvard University Press, 2004), 4.

[4] Rogers explained that these photographs “were taken with a variety of 35mm reflex and rangefinder cameras – the better ones sold to raise money when times were tough and replaced with junk shop finds until funds flowed again. Stuart Page very kindly loaned me an OM1 for a very extended period. All processed and printed in home darkrooms of the "cupboard under the stairs" variety in many locations.”

[5] Burke, Andrew. Nation, landscape, and nostalgia in Patrick Keiller’s Robinson in Space, Historical Materialism, (14(1), 2006), 4.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Martin Heidegger as cited in Žižek, Slavoj. In Defence of Lost Causes, (London: Verso, 2008), 125.

Nicholas Haig is currently a Massey University Museum Studies PhD candidate. His Marxist oriented and psychoanalytically inflected research focuses on contemporary memorial formations and the social and political functions of museums. Nicholas lives in Nelson with his wife and dog and occasionally moonlights as an art critic and curator.

Published with the support of Creative New Zealand