NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 7

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 7: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

“A collective memory contributes to a sense of belonging through knowledge and understanding of our history and culture. A vibrant cultural and national identity also helps to give a collective sense of belonging. People benefit from the social capital that documentary heritage, symbols of national identity, national events and culture provide”. - from Department of Internal Affairs 2020 Annual Report.

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Figure 7:01: John B Turner: Governor-General Sir Bernard Fergusson, Wellington, c. 1965. Work print diptych. A spontaneous performance for a photographer. Turner collection

Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au

Figure 7.02: Unidentified photographer: Cover of online Internal Affairs 2020 Annual Report. Screenshot

Most of the text in this chapter comes from selected parts of the official documentation of the various government departments. Many people may be put off by the formal nature of official documents, but they prove to contain a vast amount of information that is packaged in the digital era to make it searchable and more user friendly online. Many of the issues and services they deal with are ambitious, idealistic, and often quite complicated, but having their aims and actions spelled out allows one to measure their successes and identify issues that they have not addressed. From my research, the overall governmental failure to plan for saving analogue photographs of significance from the period 1950 to 2000 heralds a potential disaster for the documentation of our visual heritage and demands urgent attention by all authorities and individuals concerned.

The Department of Internal Affairs has the overriding responsibility for both the National Library of New Zealand and Archives New Zealand and, also reports to the Government on the role of various institutions tasked with ‘preserving New Zealand’s documentary heritage and ensuring a full and accurate public record is created and maintained’. Their 2020 Annual-Report makes no mention of preserving pre digital photography or other visual records, but the top-down directive and enthusiasm for moving to digital means of recording is clear.

The Report records that they ‘supported 144 public libraries to provide easier community access to online information and services, through a technology refresh of the Aotearoa People’s Network Kaharoa’, and ‘made over 720,000 new digitised items available through Archives New Zealand and the National Library’s online services.’:

Government use of Cloud services

‘Cloud technologies, from data storage and computing power to Cloud-based tools like Zoom and Microsoft Teams, are a key building block for digital government and we have continued to support the public service to use these technologies.

We have established a work programme to support agencies to accelerate the use and recognise the benefits of Cloud services. This work programme focuses on improving New Zealand’s access to onshore and offshore Cloud services, adjusting public service settings to better enable Cloud use and supporting agencies to use Cloud services successfully. The programme is governed by the Government’s Functional Leads, and a cross-agency working group of senior officials has been formed to support the programme’s progress’….

CASE STUDY Coordinating agency ICT investment

‘Work carried out by our Digital Public Service branch (DPS) in 2019/20 has highlighted government agency intentions to spend more than $3 billion on ICT [Information and Communication Technologies] and digital over the next five years, making a coordinated, principles-based approach all the more important to ensure value for money, and benefits for the wider system in delivering for New Zealanders’.

The National Library is one of their recipients, regarding which they state:

National Library online services

‘A continuous cycle of user-driven improvement has supported easier access and higher use of the collections and services that the NZ National Library delivers online. This has delivered a year-on-year increase of over 30% in the number of users and sessions on Papers Past, which provides over 6 million pages of digitised heritage content online’.

Their ‘Outcome 3 – People’s sense of belonging and collective memory builds an inclusive New Zealand’ echoes the Australian Significance study (see Part 3 of this Photoforum report):

‘A strong sense of belonging is important for New Zealand to be a welcoming and inclusive place for everyone.

Many factors influence people’s sense of belonging and connection. When people lack a sense of belonging and feel excluded, there are high social costs, not just for individuals but for communities and society as a whole.

A collective memory contributes to a sense of belonging through knowledge and understanding of our history and culture. A vibrant cultural and national identity also helps to give a collective sense of belonging. People benefit from the social capital that documentary heritage, symbols of national identity, national events and culture provide’.

Intermediate Outcomes

Collective memory is enhanced by New Zealand’s documentary heritage

A culture of reading enhances literacy and knowledge

New Zealand’s national and cultural identity is fostered and respected

Trusted citizenship and identity documents contribute to a sense of belonging

Taonga tuku iho is preserved and valued….

How we are driving change to deliver our outcomes

Collective memory is enhanced by New Zealand’s documentary heritage:

A major priority for us over the next four years is the Tāhuhu programme, which will preserve our collective memory and create a national documentary campus connecting Archives New Zealand and the National Library.

Noted under the heading of ‘The Earle Riddiford Collection’ the official report notes that:

A total of 6.46 million files were added to the National Digital Heritage Archive and Government Digital Archive, representing a 22 percent increase in preservation storage. This continues the trend of increases in storage requirements for preservation of digital documentary heritage and public records….

Accessing our archives

It’s one of Archives New Zealand's strategic aims to take the nation’s archives to the people, rather than making them come into the reading rooms. In November 2019, Archives New Zealand announced a change to opening hours across its four reading rooms nationwide (Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch and Dunedin) as a one-year pilot. This change was in response to a significant increase in demand for online records, and a decrease in demand for physical records. Reducing the hours allows Archives New Zealand to put more energy into listing and digitising records and making them available online. This increases discoverability of and provides better access to our records for a greater number of users.

CASE STUDY Tāhuhu: Preserving the Nation’s Memory

As the guardian of New Zealand’s documentary heritage and record of government since 1840, Archives New Zealand and the National Library hold irreplaceable taonga for the nation, and are legally bound to collect, preserve, protect, and make accessible this documentary heritage. (my emphasis.)

In 2015, the property project now named ‘Tāhuhu: Preserving the Nation’s Memory’ began looking at options for addressing several issues within the property portfolio for Archives New Zealand and the National Library of New Zealand. Two key objectives are to provide fit for purpose storage facilities for our physical documentary heritage and increasing storage capacity. (My emphasis. These are what several curators and picture librarians have also identified as their top priority.)

In August 2019, the Minister of Internal Affairs, Hon Tracey Martin, announced plans for a new Archives New Zealand Wellington facility at 2 Aitken Street in Thorndon. The new building will be situated next to the National Library of New Zealand and will be physically connected via an airbridge, providing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity for the development of a national documentary heritage campus. The new facility will ensure the ongoing preservation and care of New Zealand’s heritage collections and record of government. Improving the resilience of key infrastructure increases New Zealanders’ confidence in our constitutional infrastructure and strengthens our trust in government transparency and democratic accountability.

That may be so, but it also seems to privilege the Wellington-based archives.

The concept video for the new Archives Wellington is available here and a video about Archives NZ is here.

The Tāhuhu programme encompasses:

A new purpose-built Archives facility with physical connectivity via an airbridge with the National Library’s Molesworth Street facility

Alterations to the National Library Molesworth Street associated with the development of a documentary heritage campus and

A new Regional Shared Repository

Archives and National Library

‘Throughout COVID-19, access to the digital collections and resources at Archives New Zealand and the National Library through online channels were a primary focus

We experienced a sharp increase in visitors to the National Library website, with April seeing 274,000 sessions – the busiest month ever. The Archives New Zealand website also saw a significant increase in visits, with almost 72,000 sessions. The most searched item related to Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the Archives YouTube channel experienced viewing hours of 10,000 more than April and May in 2019’.

New Zealand Ministry for Culture and History

New Zealand’s cultural sector encompasses a broad range of cultural and creative industries and activities: film, music, broadcasting, design and digital technologies, our built heritage, libraries, literature, museums and galleries, performing and visual arts.

Figure 7.03: Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage: History of New Zealand photography online

Economy and Employment

‘The sector is an engine of growth for the New Zealand economy. In recent years, it has either matched or outpaced other sectors of the economy in terms of income, employment and value added.

We, along with Creative New Zealand, share a mutual interest in achieving a better understanding of the contribution the arts make to New Zealand’s economy, and also in measuring the contribution more accurately. As a first step, our two organisations commissioned Infometrics to gather information on the economic characteristics of the sector. While the findings are robust we recognise a significant portion of the arts economy isn’t captured by the data sets and the resulting calculations are conservative. The Working Paper: An economic profile of the arts in New Zealand from 2015 provides a useful start towards gaining a better understanding in this area and the data sets available will be useful in informing government policy and funding decisions’.

For more details, visit Creative New Zealand's arts advocacy page which includes comprehensive research about the nature and value of the arts…

New Zealand’s active industries delivered $6.2 billion in gross domestic product (GDP) in 2018, according to new research from Skills Active Aotearoa. Skills Active published in January 2020 the latest in its regular series of reports – the Workforce Scan. Over the course of the year, this industry [recreation, leisure, entertainment and events sectors] contributed $845 million to the economy. Sport, community recreation and aquatics was up 3.4% to 37,233 people and contributed $2.6 billion in 2018 GDP. Performing arts was up 2.9% to 29,825 people and delivered $2.3 billion to the economy.

A March 2018 report The Value of Sport released by Sport NZ, explored the value of sport to New Zealanders, their communities and our country.

It is interesting to note in relation to the issue of collecting photographers’ collections that the 2019/20 Te Pūrongo ā-Tau Annual Report (mch.govt.nz) of the Ministry for Culture & Heritage 2019/20 is well illustrated with publicity and descriptive photographs, none of which are credited to the photographer.

A last resort for heritage funding:

The Regional Culture and Heritage Fund (RCHF)

The Ministry for Culture & Heritage Annual Report 2019/20 notes that The Regional Culture and Heritage Fund is a capital fund of last resort for public art galleries, museums, performing arts venues and whare taonga (my emphasis).

‘Through the RCHF the government helps ensure buildings housing taonga, heritage and arts collections as well as performing arts venues throughout New Zealand are fit for purpose. Not-for-profit entities and territorial authorities can apply, with priority given to regional projects outside the metropolitan areas of Christchurch, Wellington and Auckland. In the four RCHF rounds announced to 30 June 2020, up to $30.139 million was granted to 17 projects across 15 regions and $28.170 million remains available for allocation to 30 June 2023. (p44)

The Ministry is the government’s leading advisor on media, cultural and heritage matters. We fund, monitor and support a diverse portfolio of 15 agencies, including Crown entities, non-government organisations (NGOs), and a statutory body.

Government makes a significant contribution to the broad cultural sector each year. Support for the cultural sector is also provided through other public sources, most notably education and local government. Further funding is provided by the Lottery Grants Board each year to four key cultural sector agencies in their capacity as Statutory Bodies. In the 2020/21 financial year we will administer approximately $577.177 million for Vote Arts, Culture and Heritage and $240.374 million for Vote Sport and Recreation.

The Ministry has a leadership role and heads an informal sector cluster of funded agencies, based on voluntary collaboration. It has been working with cultural sector agencies to develop more of a whole-of-sector approach. In addition to engaging on specific policy, research, partnerships and development areas, and aligning some funding strategies, agencies have more recently been collaborating on a range of initiatives to improve value for money and develop new sources of funding outside government.

The sector is home to tens of thousands of organisations which fit broadly into categories of heritage, culture and media’.

For a general overview of the cultural sector, read our Cultural policy in New Zealand document.

Reading between the lines, from a photographer’s perspective.

As can be seen in the official documents, there is plenty of encouragement to make photographs that help to reveal aspects of our life and times for posterity. There are many policy guidelines as well as sources of useful advice to photographers seeking to preserve the best of their work for posterity, but ultimately there is no guarantee, nor one way, to ensure that our visual legacy will survive. And whether it deserves to survive, in part or more, is another issue, and one seldom talked about.

Exhibitions, photo albums, books, magazine articles, films and interviews can help to draw attention to some aspects of our vision and experiences, but as archivists know, there is more to it than that. And, most importantly, the value of the records will depend on what questions are asked by unborn generations. Obviously not everything can or should be saved. Or rather, not everything produced by everybody can or should be preserved; but it can help to have the broadest and most liberal samplings available for inspection in the future to represent the breadth and depth of increasingly large bodies of work.

No matter how well policies and guidelines are worked out with the best intentions, the nature of pictorial records and their actual or potential use-value, it seems to me, will always challenge expectations, definitions, and descriptions. A personal decision will have to be made by somebody, or a team charged with the responsibility. Saying yes could be more difficult than ever before, based not simply on the sheer number of contending items, but also because of the growing awareness of the expressive value of even the humblest snapshot, which makes the library and museum, (seldom the art gallery) the depository of the majority of significant historical photographs. Why we do not recognise this is because the picture/history experts in the libraries and art museums are rarely available or supported to make their curatorial research public. Just from my observations while seeking suitable homes for both my own 60 years of photography and also Tom Hutchins’s collection, there is usually the relentless backlog of un-accessioned and uncatalogued work that the experts feel obliged to prioritise before adding more collections to process, and every delay means there is an increasing danger of valuable collections falling between the cracks.

I know that my personal photographs: of youthful interests, family and friends, growing up, marriage, children, work trajectory, leisure activities and so on will be typical of many of my generation and perhaps better photographed by others. But one point of difference is that I developed an interest in the history of photography which opened my eyes both to worlds I hadn’t experienced, and the diversity of approaches one can take, whether consciously or unplanned. As the great US photographer and filmmaker Paul Strand noted, “We can only say what we see”. Which for me first meant enjoying and learning from other people’s work and later finding ways to help them to gain recognition for their special talents and the content and form of their work. The wider society can be slow to respond, so I still find it surprising that so few of our remarkable pioneer photographers have been represented with even modest monographs, let alone online portfolios of substance to introduce their work.

Thus, I have enjoyed including examples of work by a few of them in this investigation which is liberally illustrated from work in my own collection and Tom Hutchins’s because it is readily available and waiting for adoption. I know of many a collection that could have been utilized but the point I wish to make, and the one that concerns me most, is that I have seen few signs to suggest that there has been any attempt by heritage collecting institutions to seek and ensure that a large number of outstanding photographer’s collections from my post WW2 generation will be saved for posterity. That is a shocking prospect.

Generally, I think we photographers have a reasonable idea of the merit of our work across a wide range of content in regard to recording our lives, but for future generations, the decisions about what will or won’t be preserved is slipping out of our hands, year by precious year. But once alerted to the myriad ways in which a photograph of something can prove useful to somebody in a way we could not have imagined, it becomes more difficult to personally assign significance or relevance and nowhere near as clear-cut as deciding which images best represent one’s artistic intentions.

Acknowledging how much we do need the help of informed advisors to adjudicate on significance, I was tempted to put boxes for Save, Destroy and Undecided next to every picture included in this investigation for concerned readers to share their judgement. To which might be added a Toss the Analogue Print and Keep a Digital Copy! tick box in keeping with a dangerous new trend.

But seriously, how else can I or anybody else know what New Zealand’s picture librarians and curators think about the use-value of my digital photographs of China made since my first visit in 2007 and since? By which I mean not all of them but any selection I make to express something about my lifestyle in this different country – the measure of which is how different or similar certain aspects of daily life can be and what they look like. As a pakeha New Zealander, I feel blessed to have grown up with Māori and Pacific Island peers with their own distinct cultures and histories – and acknowledge the patently unfair treatment they have too often received from the settler communities reluctant to adopt different and better ways of doing things for the common good, such as restorative justice.

For what it is worth, I see my photography here in China, and the more limited work I was able to do decades ago during visits to North America, the UK and Europe, as a continuation of my approach to documenting aspects of everyday New Zealand. My main interest is to show aspects of the familiar and typical, warts and all - rather than create romantic and idealistic depictions or art for art’s sake (with occasional exceptions).

Where do photographs like the two examples below, made by a New Zealander living in a different country, fit in, if at all, with the collecting policies of New Zealand’s cultural archives?

Who decides on what grounds they should be accepted or rejected outright, or recognised as significant in some way as a potentially useful reference to New Zealand’s history and culture?

These are just two examples of the kind of complex questions confronting picture librarians and archival experts charged with preserving aspects of our cultural heritage every day which never seem to be discussed with practitioners.

Figure 7.04: John B Turner: Valentine's Day flowers, Mingjia Gardens, Changping, Beijing, China, 2012. (JBT©20120301-038)

Figure 7.05: John B Turner: Night vendors, Tiantongyuan North railway station, Changping, Beijing, China, 2012. (JBT©20120229-1143). Providing instant foods and other products to hungry commuters, this unruly conglomerate of independent vendors was soon removed by the authorities. A few orderly semi-permanent stands later took their place during the period that saw the railway station and adjacent bus terminal rebuilt to improve the heavy traffic flow

I think there is value in comparing like with like as well as concentrating on difference. A typical rural street in parts of China is barely different from one in New Zealand in essence and the same can be said of many city streets. The difference is likely in the architectural details; obviously in the signage language, and perhaps also in the different presentations of the same merchandise; the things sold all around the globe with minor design variations and different labels, like an electric hot water jug or toaster. Cities are cities, and except for those like Venice or Pingyao (one of China’s preserved ancient walled cities), most display an up-to-date international flavour and clusters of remains of historical importance.

The greatest variety, diversity, and wealth disparities are perhaps on show side by side in the suburbs where families create their own idea of livable surroundings according to their means, interests, and imagination. Culture, I think, can be seen as a chain of habits caused by circumstances over thousands of years that lead to the same things, like the food we eat, to be cooked, presented and eaten in noticeably different ways.

Words are vitally important and so is the way in which they are delivered because they require interpretation and sometimes reading between the lines to properly understand. Irony and humour, for example, are easy to be mistaken if only literal meanings are understood. On top of which it is important to remember how language and concepts are inextricably linked and affect how we think. When we communicate in a second language the likelihood of not being accurately understood by a native speaker is, I think, likely to be increased. Not only is accurate translation exceedingly difficult to achieve, the process often reveals that there is sometimes no equivalent word/concept in a language to express certain things in a different one. And it doesn’t make things simpler to discover that the very same word means something different in another language, just as the tonal emphasis can radically alter meaning for the spoken word. The accurate translation of Chinese into English and vice versa, for example, is a huge challenge fraught with potential misunderstandings and blunders that can’t always be comprehended or laughed off. Even wordless pictorial illustrations like cartoons are susceptible to misinterpretation from those who are not in the bubble (the know).

Photography, like all visual media, has its own language, which is why John Fields called the collaborative 1970 publication he initiated Photography – A Visual Dialect: 10 Contemporary New Zealand Photographers, because we were particularly conscious of the gaps between the dominant word-oriented populace and visual creatives like ourselves when it came to expressing our views in pictures. For better or worse that gap has been narrowed by new technology and visual media to the point that we are flooded with visual signals too fast, and too fuzzy when frozen in time, to critically inspect and objectively analyse for ourselves.

What then can photographers of my generation expect from those officially charged to decide on which of our photographs are worthy of preserving for posterity as actual objects or digital copies or substitutes? At present, the names, experience, and qualifications of those tasked with deciding which, if any of one’s photographs will be adopted for a public collection is virtually a secret. Their methods of selection are unknown and despite looking, I have yet to sight any account describing any discussion of the pros and cons regarding any such adoption or rejection of specific items from a particular collection. We are being told that some organisations are applying the guidelines proposed by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth in Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, which was introduced in Part 3 of this investigation but if so, there seems nothing transparent about the process in New Zealand.

From personal experience I know and generally trust the discernment of many of our picture specialists and admire what they have managed to collect over the past 50 years. But at the same time, I also share their frustration at the many restrictions, particularly in terms of finance and personnel, that lead to excluding significant images and bodies of work, such as those examples mentioned in this review. I am inextricably drawn to the conclusion that despite, or because, of all the good words about the value of our visual heritage, there is no evidence that the government leaders who are supposed to be supervising this aspect of our visual heritage have any idea of the current crisis outlined in this survey, let alone an understanding of the nature of the problems that need to be urgently tackled and resolved in collaboration with the groups and individuals concerned.

This then, is a plea to the powers-that-be to acknowledge the concerns of picture librarians, curators and practitioners that there is a crisis in the making caused by inadequate planning for the collection of photographers’ analogue collections by our public heritage archives in the new digital era.

That a responsible Department be tasked in collaboration with picture specialists, collecting institutions, the photographic and art communities, and individual practitioners to investigate the situation.

That a guiding list of significant photographer’s collections worthy of consideration for heritage archives be drawn up for systematic analyses and ranked for relevance, risk and urgent action.

That the specialist staffing of key heritage archives be increased and facilities improved to ensure not only that significant bodies of work from the latter half of the 20th Century can be vetted but also documented, archived and made available in the appropriate manner to represent a period of vital activity in documenting New Zealand in a new way by a new generation.

That adequate new funding is set aside for this purpose.

External affairs?

Where can these photographs fit in a New Zealand heritage archive?

A related issue for context and significance regarding non-New Zealand content is to do with what individuals collect as evidence of contact with people in the rest of the world, as art works, comparisons, and reminders, to do with the support, challenges and inspiration that helps us to progress our own interests and skills.

For this reason alone, serious consideration needs to be given not only to an individual’s body of work but also to other’s saved work that may have consolidated or changed the direction of their work, interests and methods.

In the mix of images below, which are all in my collection, I briefly comment on key aspects of their meaning to me, and why I still hope to find a collecting institution that also sees meaning and connections of the kind that social and art historians, students and novelists might enjoy.

Figure 7.06: George Ward (UK): Dirk Bogarde in A tale of two cities, 1954. Autographed on verso, 1958. Turner collection

As a schoolboy my first love was the movies; British films mainly, and I earned pocket money from selling ice-creams at half-time at the Prince Edward Theatre in Woburn, Lower Hutt, where I also helped put up the stills, posters and titles advertising the films. I sought autographed prints from favourite actors and actresses and learned to distinguish between a signed and merely stamped signature from them. Learning how important the role of the film’s director was, I wrote to Betty Box and Ralph Thomas from the Rank Studios and received their authentic signatures. I was also thrilled to receive from David Lean a promotional booklet and a film script from The Bridge on the River Kwai when I asked about his work. The less glamourous behind-the-scenes creatives in the industry, I found, were willing to answer serious questions from far away.

Figure 7.07: Paul Strand: Bent Grass, Machair, Isle of South Uist, Outer Hebrides, 1954. A signed gravure from his book Tir a’ Mhurain. Turner collection.

A decade later I was writing to and about famous photographers – reviewing their books and enquiring about the price of their prints. Paul Strand, living in France, was a generous correspondent and wanted to know what the New Zealand photography scene was like. He rightly assumed that his print prices were out of my reach and kindly sent me four signed and lightly over matted gravure reproductions from his latest book, Tir a Mhurain (1962). I had told him why my super favourite images were two of his portraits and one interior from the series and being a consummate editor of his own work, he taught me a lesson by including the landscape image (Figure 7.07 above) to stress the importance of the environment his subjects lived in. One which was then threatened by the addition of a British nuclear facility, as I later learned.

Figure 7.08: John B Turner, 1969. My framed photograph of Edward Weston’s Civilian Defense, 1942, printed by Cole Weston. Detail from proof sheet. Turner collection.

Nancy Newhall’s Aperture monograph Edward Weston: The Flame of Recognition (1958) which I discovered a decade later, and The Daybooks of Edward Weston (1973) which she edited, were immensely influential around the world, not least because they included a chronicle of his model/lovers as well as the genesis of so many of his sensuous photographs.

Nobody, I think, had described so intimately the daily life of a photographer so intent on simplifying his life to enable him the freedom to make photographs to satisfy himself. He became a romantic hero for many who dreamed of living off their artistic output – in photography – and in so doing became the head of a dynasty of independent photographers.

Edward taught his youngest son, Cole Weston, how to print his negatives the way he intended and to continue to make his prints available at an affordable price after his father’s death. I bit the bullet and chose to buy what was then considered a difficult image – even an aberration - by Beaumont Newhall, the prominent art historian of photography and husband of Nancy. I saw it as highly affective satire relating not only to his criticism of war but also to his beginning as a photographer in the romantic tradition of Pictorialism (aka “art” photography). It was a typically gorgeous full-toned gelatin silver print that gave the illusion of “the thing itself” which is one distinguishing quality of the medium.

I bought the print with the required import license, framed it, and continued to enjoy it. I showed it to numerous photographers as an exemplary classic contact print and, unfortunately, broke the glass and put a nick in the surface of the print when bringing it home from teaching a photography workshop. Notably, it was seeing this print (in its pristine state), according to Peter Peryer, that inspired him to become a serious photographer.

When Cole Weston was planning to tour New Zealand with an exhibition of his father’s photographs in 1976, I persuaded him to bring one of Edward’s negatives and demonstrate how he printed them at a workshop for the Elam School of Fine Arts. This slightly dark reject print did not warrant the full archival treatment, but Figure 7.09 includes the standard printing notes on the back of it.

Figure 7.09: Back and front view of a reject print made from the original Edward Weston negative of Cypress Trunk, Point Lobos, 1930, by his son Cole Weston for a printing workshop at the Elam School of Fine Arts, 1976. Turner collection

Figure 7.10: Michael A Smith: Near Blue River, British Columbia, 1975. Turner collection

When Michael A Smith and I first met in the USA in 1980 he had already seen Photoforum magazine and indicated a strong desire to visit and photograph in New Zealand. He also gave me two landscape prints made in the classic style of large format “straight” photography to add to my collection. I met him again during my 1991 stay in Arizona but by the time he got to New Zealand with his partner, fellow photographer, teacher and publisher, Paula Chamlee, it was 2016 and I was living in China. We did manage to connect at Auckland airport, however, on the day they flew home after their hectic working visit despite Michael’s declining health. He died in 2018, but their inspiring publishing partnership lives through the brilliant publications of Lodimer Press and the workshops that Paula continues.

Figure 7.11: Graham Howe: Art is Fine, Photography is OK greetings card, c 1980. Turner collection

‘Art is Fine, Photography is OK.’ is stamped on the greetings card I received years ago from Graham Howe, who was the dynamic founding Director of the Australian Center for Photography (1973). His T-shirt message reads “Personally, I feel photography is primarily to do with communication, and that arty-crafty and esoteric mumbo-jumbo is strictly for the birds.” But the name of the person quoted and apparently responded to is unreadable.

Graham went on to become a curatorial and publishing specialist, starting with the organisation of the Graham Nash Collection from 1977-1988. We have many interests in common regarding the histories of photography and publishing but have not met for 50 years and only occasionally communicate while we get on with our own projects. I admire the surveys of Australian contemporary photography he did for the ACP and what I have seen of the books he has since authored and this care is a reminder to keep an eye on his work.

Figure 7.12: Frank Schwere: New York, 9.11.2001. Turner collection. Courtesy of the photographer

Frank Schwere was living in New York City on “9/11” (11 September 2001) when the twin towers of the World Trade Center were attacked in a suicide mission by al-Qaeda with hijacked commercial airliners. I was moved by the haunting beauty of his photographs of the devastating aftermath of 9/11 which he showed in a pop-up exhibition in Auckland’s upper Symonds Street about a decade later and bought a print. Frank was born in Germany and studied photography in Bielefeld, a West German industrial city. He lived and worked in Berlin from 1993-1997 before moving to New York where he was based from 1997-2009 before moving to Auckland. As understated as it is, this photograph, which resembles a scene from a movie, still triggers shocking memories. Despite its visual beauty, it is not an image one would want to hang on the wall for long. Today, with that event being so widely documented, it raises the question, despite its significance, of whether any New Zealand public archive would wish to add it to their collection?

Figure 7.13: Tom Hutchins: Boy walking to photographer, Shanghai, China, 1956. (C004-21a), Tom Hutchins Images / Turner collection

This picture of a friendly little Chinese boy coming to greet a foreign photographer - to the delight of his parents and curiosity of a small onlooker – is one I hope to be able to rescan. This is a rough and cropped version from the original 35mm negative scan which has digital streaks in the sky area and is not good enough to exhibit or publish. It is one of hundreds of Tom Hutchins’ photographs of China in 1956 that he did not personally nominate as among his most significant 600 images from around the 6,000 frames he exposed. My first priority now is to complete the kind of book Tom wasn’t able to make, based on his eye-witness assessment of relevance and truth to his experience which was distorted by Life magazine’s editors when they eventually published 22 of his photographs in a nine-page feature in January 1957. When that book is completed, I will feel free to add images like this one and many others that I think are well seen and revealing. Given the choice, like other photojournalists of his era, he tended to avoid images of people looking at him instead of going about their daily activities, when in fact laowai (foreign visitors) were often a rare sight and always stood out. That was part of the reality.

Feedback and Correction (added 29 September 2023)

Part 7: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments.

1. Regarding my comments on the Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au, one correspondent was concerned that my statement could wrongly imply that the Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au has responsibility for the Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage (the funding agency for Te Papa Tongarewa The National Museum of New Zealand), which it does not.

The Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au, I am told, only has responsibility for The National Library of New Zealand/Alexander Turnbull Library and Archives New Zealand. The Ministry of Culture and History has its own ministers and funding "vote", which includes the resourcing of Te Papa, NZ Symphony Orchestra, Royal NZ Ballet, Creative NZ, Radio NZ, and many other arts organisations. Their website is: https://mch.govt.nz/.

2. The correct name is Manatū Taonga Ministry for Culture and Heritage, not "Ministry of Culture and History".

3. The National Library of New Zealand/Alexander Turnbull Library, and Archives New Zealand, while under the umbrella of Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au, is also governed by their own acts of Parliament: https://legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2003/0019/latest/DLM191962.html & https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2005/0040/latest/DLM345529.html, with these specific responsibilities set out. In the case of The Alexander Turnbull Library this includes: "to develop and maintain a comprehensive collection of documents relating to New Zealand and the people of New Zealand" (https://legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2003/0019/latest/DLM192213.html).

4. My dig that: ‘I don’t know how much it would cost but it seems reasonable that something out of the Department’s 2020 budget of $3 billion for digitising over next five years could be used to ensure that five decades of significant analogue photographs are not excluded from the historical record’ elicited the following useful clarification:

“The Department of Internal Affairs Pūrongo ā t Au (DIA) does not have a $3 billion budget for digitising heritage collections. The section in the DIA report where you draw "$3 billion" from refers to something quite different. It refers to the overall spending by all government agencies on ICT (Information and Communications Technology) and digital products/services. That is, all the government's computer infrastructure, telecommunications, etc. For their part, DIA is looking into how all this spending could be better coordinated. It is not DIA budget. To determine exactly how much is spent via DIA on digitising heritage collections you may wish to ask them directly”.

5. My conscientious correspondent points out that there is more context to “Principle Six” of the National Library Collection Policy referred to individual Collection Plans (https://natlib.govt.nz/about-us/strategy-and-policy/collections-policy). These were all developed and finalised in 2015/16, following a process of public consultation, in which different interests and communities were given the opportunity to comment and critique”, so it’s not fair solely to blame the influence of "accountants". Quite so, I stand corrected and do note that scrutiny can bear on such aspects when further public consultation on future collecting strategy occurs. It was last updated in 2015 and a review was meant to occur "no later than 5 years from the approval date".

(https://natlib.govt.nz/about-us/strategy-and-policy/collections-policy/national-library-of-new-zealand-collections-policy)

6. Lastly, none of the Library professionals I consulted mentioned the report of the National Archival and Libraries Institute’s Ministerial Group review: https://www.dia.govt.nz/National-Archival-and-Library-Institutions-Ministerial-Group which apparently elicited a large body of public feedback about the governance and funding of the National Library/Turnbull Library and Archives NZ.

The report of the Chief of the Alexander Turnbull Librarian, Chris Szekely, reiterates that their core role “records documenting New Zealand’s history and culture are collected and preserved as taonga for current and future generations, and are as accessible as possible for all New Zealanders.” His brief and worrying submission can be consulted at: https://www.dia.govt.nz/Web/DIACorp.nsf/0/FFCF5B205EC0F0B6CC2583A9000EC74F/$file/Chief%20Librarian%20Alexander%20Turnbull%20Library.pdf

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to PhotoForum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, PhotoForum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a former director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

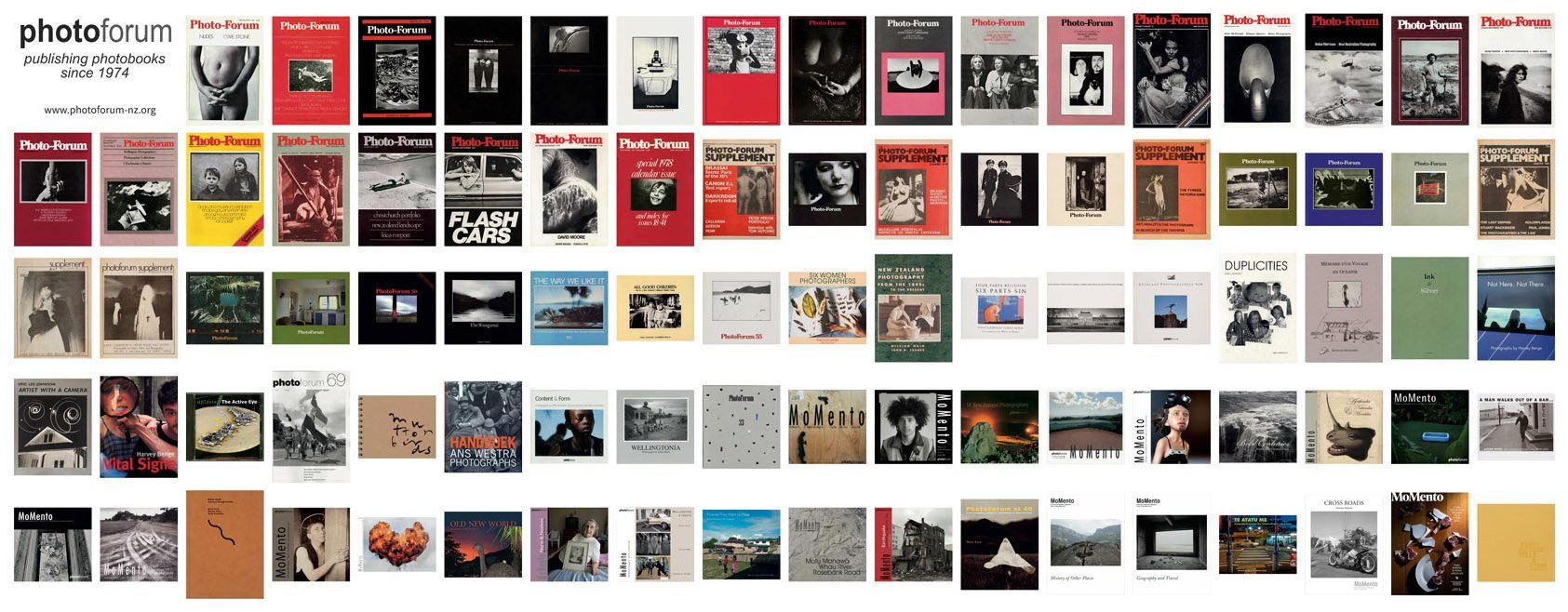

About PhotoForum

PhotoForum Inc. is a New Zealand non-profit incorporated society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression. We maintain a book publication programme, and organise occasional exhibitions, workshops and lectures, and publish independent critical writing, essays, portfolios, news and archival material on this website - PhotoForum Online.

PhotoForum activities are funded by member subscriptions, individual supporter donations and our major sponsors. If you would like to join PhotoForum and receive the subscriber publications and other benefits, go to the Join page. By joining PhotoForum you also support the broader promotion and discussion of New Zealand photography that we have actively pursued since 1974.

If you wish to support the editorial costs of PhotoForum Online, you can become a Press Patron Supporter.

For more on the history of PhotoForum see here.

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of PhotoForum Inc.

CONTACT US:

photoforumnz@gmail.com

PhotoForum Inc, PO Box 5657, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Directors: David Cowlard & Yvonne Shaw

Consulting Editor: John B Turner: johnbturner2009@gmail.com

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.