NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 8

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 8: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

“A well-organised and documented collection would mean less work (resourcing) for the institution. Similarly, a willingness to recognise the limits of most repositories would be of benefit; most collecting institutions now are likely to only select examples from larger collections rather than being able to retain the entire collection”.

Sarah Murray, Head of Collections and Research, Canterbury Museum

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Figure 8.01: Murray Hedwig: Supermarket, Atawhai, Nelson c1995. Courtesy of the photographer

Is this a significant historical photograph?

A work of art?

Both or neither?

That is what specialist picture librarians, curators, archivists, and historians are called upon to decide every day

****

Please consider the primary criteria:

Historic, Artistic or aesthetic, Scientific or research potential,

and Social or spiritual when assessing significance (i)

Canterbury Museum, Christchurch

Figure 8.02: Dr A C Barker: ‘How the world wags’ [Worcester Street], Christchurch, 10 Jan 1866. Courtesy of the Canterbury Museum. A magnifying glass was an essential tool for studying the often crucial details in a photographic image since the invention of the medium. Barker’s audience could likely read the posters in this picture and discern who the person was and whether he was working or just a prop for the photographer who was obviously interested in the real estate behind the fence and not just the pop-up show that demands a much higher resolution digital copy than this to restore the missing information with a serious zoom in on a computer. Courtesy of the Canterbury Museum. (Ref: 1944.78.291)

Figure 8.03: John B Turner: This is a rough digital cell-phone copy of an analogue copy print of Dr A C Barker’s ‘Interior of Ohapi, Orari, Feb. 16, 1870.’ Made 100 years after the original photograph, the copy print substituted for the original in the exhibition and catalogue of the ‘Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition presented by the Govett-Brewster Gallery, New Plymouth in 1970 and subsequently widely toured in New Zealand. A magnifying glass or computer zoom would degrade the details if enlarged. Courtesy of the Canterbury Museum. ( Ref: 1958.81.58)

I don’t have the original print on hand but instead include a quick cell-phone snap of it as a reminder of how copies of photographs were made in 1970 (Figure 8.03 above). The black and white analogue copy print, which was about A5 size, was made by the Canterbury Museum from a Barker album in their collection and the copy negative printed to match the size of his actual print which was about 4.5 x5.5 inches (11.5 x 14 cm). Such was the state of the art of making facsimile copies of photographic prints then.

Figure 8.04: Dr A C Barker: ‘Interior of Ohapi, Orari, Feb. 16, 1870’. Screenshot of digital online copy of the original albumen vintage print from a Barker album in the Canterbury Museum. The original print was 11.5x14cm and would have been studied with a magnifying glass, but with care a large digital print or high definition digital file could enable many of his books to be identified, and a fair charge made to compensate for that extra detail and service. Courtesy of Canterbury Museum. (Ref: 1958.81.58)

One copy print was sepia-toned to better approximate the colour of Barker’s original warm-toned albumen print and exhibited, and another un-toned version used as an illustration in what turned out to be a typically poorly offset printed catalogue at a time when commercial printers seldom saw the point of trying to make illustrations look like the original photographs and treated each one the same as a dull grey.

If I had taken the time and care needed to light and square up my rough cell-phone copy of the copy print, the result would have been a digital copy every bit as detailed, if not superior to that reasonably accurate museum copy print, plus colour, depending on the phone camera setting. Just as it is, tonally, it is superior to its catalogue reproduction of 52 years ago. Just as a screen capture of an image from one’s computer monitor can produce a serviceable copy, up to a point, that can be shared.

The relative ease with which accurate replicas of photographs and objects can be made today represents a huge advance in technology which was first perfected by the printing industry and was reflected by the growing number of illustrations of historical “black and white” photographs being reproduced in full colour for the first time to reveal their emotional as well as optical attributes.

Figure 8.05: Dr AC Barker: Maoris at Kaiapoi Dec. 17/67 (1867). From Hidden Light. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library (PA7-01-23). Screenshot. Note that the original print was cropped top and right which removed Barker’s signature and title scratched onto his wet-collodion glass negative (Canterbury Museum ref. 1944.78.241)

Figure 8.06: JHG Johns: The Upper Havelock_Canterbury, c1965. Digital copy of enlarged print made by John B Turner under the supervision of master photographer and printer, John Johns, when I briefly worked as a mural printer at the National Publicity Studios, Wellington, in 1967.

Whether made with a camera, electronic scanner, or computer screenshot, the superior technical quality of digital over analogue copies of works on paper is patently evident, as is the ease of making multiple copies. Never an exact copy with the material physicality of the original, much depends on the optical definition and nuances of colour, tone and scale for a convincing illusion of the original object as an online or printed representation. On top of which its context and provenance can provide vital clues as to its date and use, because, for instance, it was common for Victorian era pioneers to let other photographers make prints from their negatives, just as it was for the owners of prints to trim and cut them to suit their purpose.

Figure 8.07: Murray Hedwig: Wave. Birdlings Flat, Canterbury 1974. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 8.08: Len Wesney: Birdlings Flat, Canterbury 1972. Published in PhotoForum, June-July 1974. Copy from magazine

Figure 8.09: Len Wesney: On Cook Strait ferry, 1974. Published in PhotoForum, June-July 1977. This image was included in The New Photography (2019) by Te Papa curator Athol McCredie.

8.10: Unidentified photographer: Christchurch Star photographs online, Christchurch Public Libraries. Visitors to the touring Nineteenth Century New Photographs exhibition at the McDougall Art Gallery, Christchurch, 1972. From the style of these unposed photographs it is plausible that they were made for the newspaper by the late Len Wesney (1946-2017) who died in a housefire which consumed most of his digital era work but spared many of his analogue photographs

Figure 8.11: Glenn Busch: Mat King, labourer, gasworks, Christchurch, 1981. ‘Shortly after the photograph was taken he left the gasworks and went to work for the post office.’ This was the cover photograph for Working Men, the landmark book of 1984 which established Busch not only as a major photographer but also a social historian. A New Zealand National Art Gallery publication and exhibition, based on Busch’s 30-print limited edition portfolio, it was promoted by then Director, Luit Bieringa, and the printing production supervised by the master craftsman, Brian Moss, to set a new benchmark in high quality offset printing in New Zealand. Busch started off photographing and interviewing working women as well but ultimately focused on the men instead. Busch became an influential head of photography at the Ilam School of Art, Canterbury University, where he founded the collaborative ‘Place in Time’ project for which students, staff and guest photographers have combined to document Christchurch and its surrounds for posterity. Then the earthquakes of 2011-2012 unexpectedly hit and changed their place forever and once again demonstrated the value of their work which has continued with an added sense of urgency and import. Courtesy of Glenn Busch

Figure 8.12: Jane Zusters: Feminists Picnic, Hagley Park, Christchurch 1978. A multi-media artist based in Christchurch, Zusters has always exhibited photographs along with her painting and other art which deals with social and personal issues from a feminist perspective. As such, she has made important historical records of the feminist movement in New Zealand over several decades. Screenshot from Jane Zusters | New Zealand Artist. Courtesy of Jane Zusters

Canterbury Museum’s Head of Collections and Research, Sarah Murray, responded to my original four questions and one of the final duties of Dr Jill Haley, their Human History curator who recently left the Museum was to answer additional questions about their holdings which have grown dramatically in the past decade or so.

Q1. Does the Canterbury Museum have a policy statement about collecting photographers’ collections?

While the Canterbury Museum has no specific policy statement about collecting photographic collections (or any other collections), its curators adhere to collecting guidelines that include photographs. The Museum understands the value of photographic collections and has accepted large collections (such as the Clifford collection, and also Standish and Preece) when offered. The Museum collects images that are social history documents (rather than art) and related to Canterbury, the Antarctic, or the sub-Antarctic.

The Museum would assess any large photographic collections offered according to our collection plans and potentially refer large collections to another institution that collects art photography if they do not fit our collecting areas or fit with our existing collection.

Q2. What for you are the big issues that prevent the Canterbury Museum from being more proactive in acquiring collections?

Resourcing in terms of space, storage materials and staff time. To collect responsibly, Canterbury Museum limits the number of objects it acquires during a financial year to 1,500. To exceed this, Trust Board approval must be granted. Canterbury Museum counts every image (photograph, negative frame, digital image, etc.) as one object, so accepting large photographic collections can have a profound impact on the annual acquisition limit and available resources. However, in 2019 the Museum acquired thousands of negatives from the last owner of the Standish and Preece studio, which when added to an earlier donation, now totals nearly 77,000 prints and negatives from their studio. A grant from Lotteries and Heritage enabled to Museum to process this collection and make it available online. Previously, in 1980, the Museum accepted the Clifford collection, which is also comprised of nearly 77,000 negatives.*

Q3. What do you think should be done about this? Resourcing is an ongoing issue for all institutions.

Q4. What can photographers do to make their collections more relevant and attractive for institutions to collect?

A well-organised and documented collection would mean less work (resourcing) for the institution. Similarly, a willingness to recognise the limits of most repositories would be of benefit; most collecting institutions now are likely to only select examples from larger collections rather than being able to retain the entire collection.

Q5. And do you consider this is a crisis in the making, or soon could be unless (what you think could/should be done about it is done)?

In the ideal world, institutions would be able to collect large collections. However, the reality is much different. The crisis is really the larger one of a lack of funding for resourcing.

[*The Canterbury Museum’s earliest and perhaps most valuable collection, which is now online, is of the remarkable amateur photographer, Dr Alfred Charles Barker (1819-1873) who recorded many aspects of life in Christchurch from the beginnings of colonial settlement and idiosyncratic personal portraits of his family and friends. The documentation of this world class body of work, however, lags behind and stunts its use because of its old, primitive, and often incorrect identification of items from the Barker collection which includes the work of other photographers mistakenly assumed to be his.

Their central problem does indeed seem to a crippling lack of funding for staff and resourcing in this area at least. It seems inexplicably remiss that the Museum has not published a book celebrating Dr Barker’s work 50 years after Cotsford C Burdon’s lightweight Dr A. C. Barker 1819-1973: Photographer, Farmer, Physician was published by John McIndoe in Dunedin in 1972.

[Note: The Christchurch City Libraries were not included in this initial survey, but recently they added Doc Ross’s photographs of Christchurch, before and after the earthquakes of 2010-2011 to their digital archive at https://canterburystories.nz/collections/archives/docross ]

Figure 8.13: Joan Woodward: Aulsebrook's flour mill Antigua Street, Christchurch 1985 - demolished Jan 1986. Screenshot from Canterbury Museum online. Joan Woodward was the Museum’s former photographic librarian who became a respected photo historian. Courtesy of the Canterbury Museum. (Ref: 1997.258.328)

Figure 8.14: Tim J Veling: Support Structure 2, Christchurch Cathedral 2011, from A Place in Time. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 8.15: Hanne Johnsen: Image from ‘The 9th Year’ project by the then Ilam student who documented year nine students from five Christchurch secondary schools. Screenshot. Courtesy of the photographer and Place in Time project

Figure 8.16: Contents page of Place in Time website by Ilam School of Fine Arts photography staff and students. Screenshot with photograph by Haruhiko Sameshima, Courtesy of Place in Time

Figure 8.17: Doc Ross, untitled, from his series, ‘The Empire is in Ruins’, 2011, after the Christchurch earthquakes. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 8.18: Doc Ross: untitled, New Regent Street, 2012. Courtesy of the photographer

Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

Ken Hall, who is one of the curators at the Christchurch Art Gallery, studied photography at the Wellington Polytechnic under the photo historian William Main and has since worked on numerous photography exhibitions and publications, including work by contemporary New Zealand photographers David Cook, Neil Pardington and Yvonne Todd. In 2004 his landmark monograph, George D. Valentine: A 19th Century Photographer in New Zealand was published in association with a touring exhibition produced by the Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu, and in 2005 presented an exhibition of work by the famous US champion of photography, Ansel Adams. In 2019 the Gallery presented a distinguished but hard to find Ken Hall survey exhibition and book, Hidden Light: Early Canterbury and West Coast Photography, which regrettably did not tour. Haruhiko Sameshima wrote an introduction to the short-run book, and the good news is that it can be downloaded as a handsome PDF here! Deservedly, though rather belatedly Hidden Light won the Art Association of Australia and New Zealand (AAANZ) award for the Best Medium Exhibition Catalogue in 2021. (“Medium” referring to its size, not quality.)

Too busy earlier to properly respond to my basic questions, Ken Hall got back recently with a few points about their situation. To start with, he said, their focus tends to be more towards exhibiting artists’ work than on collecting and archiving it, in the way the Turnbull Library and Dunedin’s Hocken Library do, and he is aware that archives like theirs “are often overwhelmed by the amount of material being offered, made, or turning up”.

He’s not sure if it’s a crisis in the making but thinks it’s up to individual photographers to make contact with the institutions that look or seem like the best fit to work things out in a way that makes sense for them.

“I would say that Christchurch Art Gallery is not well placed to bring in large collections of photographers’ work, unless it is streamlined, ‘packaged’, edited. I am thinking of Ansel Adams and his Museum Set as an exemplary piece of planning, being the100 photographs he considered his best, or most broadly and usefully representative [as perhaps] something for others to take cues from?”

Working with one Christchurch photographer, recently, he said, he and a colleague were “able to narrow down the selection to almost 20 works, all of which are seen to have exhibition potential. If offered his whole archive, however, this would likely be beyond us – we would certainly be overwhelmed, for reasons including storage space and resources – financial and staffing. Both are always stretched.”

This to me, is a reflection of the relatively rarefied atmosphere most art galleries exist in when it comes to the big picture involving the preservation of whole collections and it is entirely understandable as the rationale for a financially strapped regional gallery working to make the best use of its curatorial talent. But one problem with this kind of cherry picking, is that it relies on other institutions, like the Canterbury Museum, to tend to the whole orchard created by the likes of Dr Barker in the 19th Century, and people like Glenn Busch, who started Snaps – A Photographers’ Gallery in Auckland in 1975 and went on to create the increasingly valuable ‘Place In Time’ documentary project on Christchurch with his photography students while teaching at Canterbury University.

To only preserve 20 images from such projects would totally miss their documentary value as visual evidence of our life and times, which was so tragically illustrated after the disastrous earthquakes that destroyed so much of the city and surrounds. Reconstruction, and current battles with the Covid-19 pandemic, are now being documented for the Place in Time project under the direction of Tim Veling, a former Busch student who now heads the Photography department of the Ilam School of Fine Arts.

The famous US photographer and conservationist Ansel Adams, mentioned by Ken Hall, however, is an apt model for doing all one can to celebrate and preserve a worthwhile legacy. To select no more than 100 of one’s photographs from thousands is inevitably a daunting and chastening exercise – a test guaranteed to question the social and artistic relevance of one’s legacy. Adams, an exceptionally versatile and prolific practitioner, ensured that his negatives would be preserved as part of his legacy, because he envisioned a future when, perhaps, his negatives could be printed better than he could. Unlike Brett Weston, Edward Weston’s eldest son, who chose to destroy his negatives perhaps because his ego told him that nobody could print them like he could.

Adams did not predict the coming digital revolution, which I think would have excited him no end, so in 1956, his bequest to the Center for Creative Photography, which he helped establish at the University of Arizona in Tucson, included his negatives.

The Center for Creative Photography’s archive is one of the best in the world and includes the archives of other luminaries such as Richard Avedon, Harry Callahan, Aaron Siskind, W Eugene Smith, Paul Strand and Edward Weston; along with those of art historians including Bill Jay, Beaumont and Nancy Newhall and Naomi Rosenblum.

Just this month (January 2022), while announcing their acquisition of the archive of Lola Álvarez Bravo they noted that Ansel Adams’s negatives, which began arriving in 1976, and ‘are currently inaccessible due to renovations in CCP's cold storage facility…. will be accessible once the renovation is complete and the negative boxes have been relocated to the new frozen storage space. The estimated date of availability is August 31, 2022, although not guaranteed.’

Which leads me to speculate on the viability of the CCP setting up a fund-raising challenge for the long list of Adam’s admirers to have an opportunity to improve on his printing by digital means? Or to rent out his negatives world-wide for such a purpose?

Rather than restrict itself to only showing work that it owns, the Gallery borrows photographs from numerous libraries, art galleries and private collections for its carefully curated exhibitions of historical and contemporary works.

Figure 8.19: George D Valentine: Pohutu Geyser, Whakarewarewa (GV276). Courtesy of private collection

Figure 8.20: John HG Johns: Burnt Corsican pine, Balmoral, Canterbury, 1955. N.Z. Forest Service. John Johns was a brilliant photographer without artistic pretentions who in his 50s enrolled for a 1980 US workshop by the famous photographer and conservationist, Ansel Adams. Adams recognised him as an equal and they became friends.

Figure 8.21: John HG Johns: Virginia and Ansel Adams at their home in Carmel, California, USA 1980. Turner collection

Figure 8.22: Ansel Adams: Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, California 1944. Courtesy MOMA, NY Screenshot

Figure 8.23: J J Kinsey: May Kinsey climbing an ice face 1895. ATL (PA1-q-137-20-2) Screenshot. From Hidden Light, Courtesy of Turnbull Library. May Kinsey, here photographed by her father, was an accomplished photographer in her own right

Figure 8.24: Charles H Monckton (attributed): Foot Race, Half-Ounce, Totara Flat, West Coast, c1871. From Hidden Light, courtesy of Barry Hancox collection

Figure 8.25: Edmund R Wheeler: Wool Sorting Horsley Down, Canterbury, 1880s. From Hidden Light, courtesy of a private collection

Figure 8.26: David Cook: Screenshot of photograph from the book, Meet me in the Square, a retrospective look at Christchurch in the mid-1980s before the devastating earthquakes of 2011-12. Exhibited and published by Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetu in 2015. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 8.27: Tim J Veling: Cathedral Square Markets, Christchurch, 2020. From A Place in Time. Courtesy of the photographer

Endnote: Part 08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery Te Puna o Waiwhetū

(i) Based on criteria proposed by Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth in Significance 2.0: a guide to assessing the significance of collections, Collections Council of Australia Ltd, 2009: ‘Four primary criteria apply when assessing significance: historic, artistic or aesthetic, scientific or research potential, and social or spiritual. Four comparative criteria evaluate the degree of significance. These are modifiers of the primary criteria: provenance, rarity or representativeness, condition or completeness, interpretive capacity.’

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to PhotoForum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, PhotoForum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a former director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

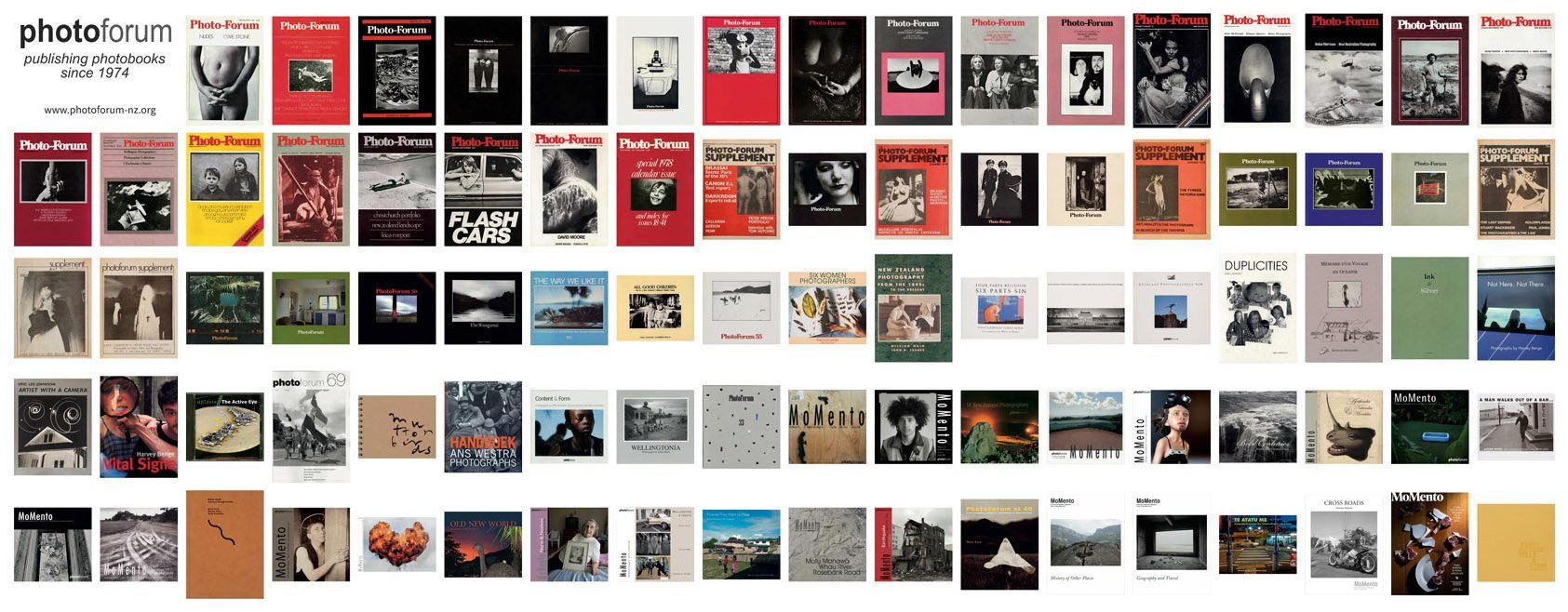

About PhotoForum

PhotoForum Inc. is a New Zealand non-profit incorporated society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression. We maintain a book publication programme, and organise occasional exhibitions, workshops and lectures, and publish independent critical writing, essays, portfolios, news and archival material on this website - PhotoForum Online.

PhotoForum activities are funded by member subscriptions, individual supporter donations and our major sponsors. If you would like to join PhotoForum and receive the subscriber publications and other benefits, go to the Join page. By joining PhotoForum you also support the broader promotion and discussion of New Zealand photography that we have actively pursued since 1974.

If you wish to support the editorial costs of PhotoForum Online, you can become a Press Patron Supporter.

For more on the history of PhotoForum see here.

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of PhotoForum Inc.

CONTACT US:

photoforumnz@gmail.com

PhotoForum Inc, PO Box 5657, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Directors: David Cowlard & Yvonne Shaw

Consulting Editor: John B Turner: johnbturner2009@gmail.com

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.