NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 4

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance, & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 4: Gael Newton: Parting with your art, & Photographers’ Archives

“Current collectors hoping to pass their material on to a public collection in the near or distant future should consider a plan B, and even a plan C or D.”

Figure 4.01 W H Fox Talbot: Bookcase at Laycock Abbey, Bath, England, 1839. Salt print from paper negative (image 14 × 19.9 cm). Courtesy Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, USA. Gilman Collection. Screenshot

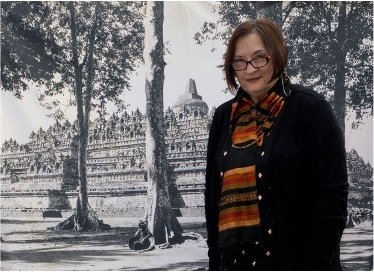

Figure 4.02: Paul Costigan: Gael Newton, curator of Picture Paradise, Asia-Pacific Photography 1840s – 1940s, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, 2008, Courtesy of the photographer

Parting with Your Art: A curator’s perspective by Gael Newton

While sourcing information for this article I discovered that Gael Newton, the Australian curator and art historian has been writing about some of these issues on her lively blog under the category of ‘Parting with Your Art’ (Gael Newton (photo-web.com.au) since she retired from the Australian National Gallery in Canberra in 2014. With extensive experience in the myriad aspects of collecting and promoting photography as an art, she generously shares her discoveries in a down to earth Aussie way.

Having been a museum curator, then valuer, seller and donor to museums and libraries, she explains how she and her partner Paul Costigan are now disbursing their large library and photo collections built up over decades. Seeing that there was not much online for people with collections, she decided to write about the options and processes involved in placing their treasures in new homes by sale or gift. And in the process has had a rush of responses from photographers, about what they should do with their archives.

“Why am I doing this?” she asked. “A while back — after a few of my contemporaries passed away — I thought I’d rather know where my stuff was going and not leave it to others [to sort out]. Like bush fires its best to have a plan as life doesn’t always go quite as expected. But it is also emotional as the books are also about aspirations and seeming to erase my personal history.”

Figure 4.03: Screen shot detail of my July 2013 blog about the late US, Canada-based photographer Dave Heath and our print swap in 1969

“It has been a challenge to find homes for books and prints and the amount of work is the same for gifts and purchases”, she notes, and owns the sense of grief that accompanies the departure of her treasures. As of July 2021, she has discussed many of the big issues in separate posts, including:

· Managing expectations and large collections

· Books — distributing a collection of books

· Some guides to cultural gifts program donations

· Photographer’s Archives

· Capital Gains Tax (an introduction only)

· Downsizing Collections — sale of Artworks and Books

· More on Capital Gains Tax

· Finding New Homes for My Library

Because I’m going through this selfsame process, I have already benefitted from some of Gael’s advice and example. And by way of disclosure, I’m proud to say that Gael Newton was an Elam School of Fine Arts student who studied art history with Tony Green and photography with Tom Hutchins, Max Oettli and myself during my first years there in the early 1970s. Thereafter she embarked on a distinguished career as a photographic curator and historian. Slightly bemused to hear recently that she had donated a modest collection of 19th Century New Zealand vintage photographs to the Auckland Public Library in my honour I was later chuffed to see the discernment that had gone into her selection of cartes de visite and cabinet prints and realised how appropriate her recognition of a former teacher with shared interests and enthusiasms was.

Books: the ‘extreme sports’ version of library culling

Before summarising Gael’s advice about disbursing photographs and photographer’s archives, I would like to share a few of her comments about the dispersal of books, which she calls the ‘extreme sports’ version of library culling. Make of them as you wish.

· I have come to have an ecological epiphany and believe that what I paid to bring into the house, I should also be prepared to pay to distribute. I like the idea of the baton being passed to a new or different scholar. There have been moments of real pleasure in a book going to an enthusiastic new owner.

· You will find that second-hand bookshops don’t take books these days even as gifts, so charity book fairs like Lifeline [in Australia] provide the easiest opportunity for your treasures to find a new home. (I will inquire what percentage of the donations are pulped).

· Over the last year or so I have cleared one room’s worth of bookcases by a combination of strategies of donations to friends, colleagues, and former interns as well as public archives.

· Disposal Process: About once or twice a month I grab a load of titles from the shelves and use the National Library’s TROVE search engine to see which of my favoured Australian libraries don’t hold a copy already…. I double check the intended library’s online catalogue. The last thing the librarians want is a box with lots of books they already hold. I send the TROVE links to the chosen librarians asking which ones they want.

· The books then go into tubs under the desk with institution names on. When the tub is full the books [they] are boxed, labelled, measured and weighed for Australia Post parcel [delivery] and finally put aside for the next post office run.

Before getting to the most pertinent category of Photographers’ Archives, I think it is useful to mention her blog on downsizing collections, dealing with sales and donations of books and photographs.

Downsizing collections: Sales and donations of books and photographs

Because Gael has not tried book auctions or asking a specialist art book dealer to come and assess what is saleable, this blog item is perhaps of limited use. But she is always open to contributions on aspects she does not cover to add to her blog. Aside from the fact that she and Paul are financially able to gift much of their collection, a situation that not everybody will enjoy, she makes some interesting points:

· Over the past decade I have gifted books and art works to friends, professional associates, interns, and even to long term researcher correspondents and photographer-descendants. I do so while encouraging them not to put the prints away in boxes but to enjoy them on display…. Sometimes perfect preservation isn’t the only life a print can have.

· The responses have often made the exercise doubly satisfying… and gifts to artists have also given a sense that the work was going somewhere where it would be appreciated and viewed regularly. I sometimes get snaps from recipients of works on display.

· There have also been gifts to museums in honour of friends; an Olive Cotton view out the Clarence Street studio on 1942 when she was manager during Max Dupain’s wartime absence has gone to the art collection at my alma mater — Sydney University, in memory of the art historian Dr Joan Kerr.

· I have also followed my own advice and taken small groups of favourite works out of boxes and having them framed. We are now planning to get rid of all tall cabinetry so as to have more wall space for a salon style hang.

· If your books are mostly from your own lifetime there is a good chance most art libraries already have a copy.

· Every book disposal option costs you time and probably money. Think laterally, ask art schools or universities if you can put boxes out for students. Offer mint copies to an art centre with a shop as quality pre-loved copies.

· Scour the shelves for books that might appeal to someone you are meeting.

· I bought a weighing machine (similar to what is used in post offices) and have armed myself with a cutter, numerous tapes and bubble wrap to protect good book corners from damage in transit.

· Public libraries rarely take collections unless of especially rare or specialised items and you need to provide a detailed listing first and pay the transport.

Figure 4.04: John B Turner: Some of my books up for sale during my dual exhibition: a selection of my own photographs and a selection from my collection of historical and contemporary photographs from NZ and elsewhere. Bowerbank Ninow Gallery, 10 Lorne Street, Auckland CBD, 30 January 2020. (JBT20200130-0072). The gallery under the same ownership has since changed its name and staff

Managing expectations and large [collector’s] collections: Facing off large collections

This item from Gael’s blog relates not to collections of a single photographer’s work but mainly to collections of art by multiple authors. It is thus relevant for those photographers who have built personal collections of other practitioner’s works, so you might like to skip this chapter if you don’t have others’ work to disperse. One of the curious things about photographers that I have noted in the past is that so few of us, for whatever reasons, acquire works by other photographers even by the honourable tradition of swapping prints.

The overriding theme from Gael’s observations and recommendations is that of a changing scene in which expectations vary enormously from the owners of collections to that of the collecting institutions. She covers a range of issues that art institutes in particular, but also social history depositories are mindful of:

… There has been fifty years of rapid growth for art museum collections across the western world since the 1970s. Since that time new concepts of representing recent contemporary art, rather than already canonised older works, greatly expanded the fields of practice to be considered. Art schools flourished and produced a large cohort of practitioners.

I have abbreviated some of her points here and recommend readers to go direct to her blog for the full contents. As she says, selling or donating a collection involves too many issues and variations depend on circumstances around each collection and the collection policies and practices of individual art museums.

Figure 4.05: John B Turner: Paul Hartigan and Ron Brownson visiting the exhibition of my work at the Bowerbank Ninow Gallery, 10 Lorne Street, Auckland CBD, 30 January 2020. (JBT20200130-0072).

Things are changing

· Questions are now asked whether that level of museum collection growth over 50 years can be sustained. The growth has been greater than the extension of exhibition space.

· With each decade, fewer artists in the collection get to be shown on the walls.

· The standards of management, cataloguing storage and conservation is now far more rigorous – one might say more heavily bureaucratic or at least much more so than in previous decades.

· The public now expect extensive digitisation of collections. Unfortunately, in too many cases, these requirements have been largely unmatched by staff recruitment.

· There is a trend being introduced in some art museums whereby a work proposed by curators can be rejected at the end point on the non-aesthetic basis of longer term maintenance costs as projected by Finance, Registration or Conservation.

· With large collections, art museum’s know that some items stand a good chance of never being exhibited or viewed on request in the print room.

· The long-term sustainability approach is already discouraging the acquisition of large collections, a trend already discussed in this blog.

· Current collectors hoping to pass their material on to a public collection in the near or distant future should consider a plan B and even a plan C or D.

· A dealer once said to me ‘80% of the price of a collection is usually found in 20% of the items.’ That meant you expect to acquire low value items in order to get the top echelon.

· Any ratio like that in a collection being acquired, no matter how alluring the gems are, will be harder to justify in future.

· How can the tipping point be identified that makes a collection worth it — warts and all?

[Many of these points were also made or inferred by the NZ photography experts I consulted.]

Managing mutual expectations

A few pointers are listed below for understanding how curators might assess a collection on offer.

· The first and biggest hurdle, apart from price, is that most collections are uneven. All items are not necessarily of high museum quality, let alone a priority for the collection strengths of the museum.

· So, researching the current collection strengths or gaps of any proposed recipient is recommended.

· Understandably, having spent decades building a collection, ‘cherry picking’ by institutions is a big issue. While any collector desires the convenience of clearing the deck in one go, the integrity of the whole can be very important — even an emotional issue to them. Reasons for keeping everything together need to be articulated.

· Sometimes the collector has acquired works long before they are fashionable or appreciated by the wider art market or museums. Work by women artists might for example, have been passed over by former eras of curators.

· Curators will have priorities set from within the institution that may override the possibility that what is being offered should come into the museum’s collections — no matter what the agreed value is in money or significance.

· Taking whole collections may cause problems too big for the museum to consider taking on. For example, museum bureaucracies have no easy mechanism for hiving off unwanted items. Deaccessioning can be a long, complicated statutory process – and a bad look.

· Be prepared to negotiate about which material is not of value for the intended archive and communicate clearly that culling may in fact barely alter the asking price for the whole.

· Do push back hard against price comparisons from recent auctions as a reason to lower prices of individual items. There’s often someone in the institution’s bureaucracy that thinks that recent auction prices are the best guide. This is incorrect.

· I suggest that art museums need to recognise that the value of the collection on offer includes placing a monetary value for the totality of time spent scouting for each art object, the research this entails, and the costs of developing and maintaining a collection.

· Museums have acquired collections in the past that were barely catalogued – almost a job lot — only to find they are treasures beyond their expectations.

· Museums are also subject to fashionable whims and biases, so it also happens that works acquired and thought to be of little interest become reassessed by a later generation.

· In the 1970s–1980s renowned Australian curator and scholar Daniel Thomas[1] fought for a new appreciation of then unfashionable colonial artists. He championed the introduction of new mediums (photography) into the museum and embraced radically new art with glee. Daniel also stressed the museum is a place for the decidedly unfashionable art to enjoy quiet retirement until rediscovered.

Checklist

· Before approaching a museum, research the collection/s being approached. Can the museum make use of the size and diversity of the collection?

· Many collections have a regional focus — and not all are interested in art beyond those boundaries. Whereas others have much broader remits.

· If you are not familiar with these processes, it may save you a lot of energy to first seek advice from an outside expert. Valuers may be expensive but paying for an opinion at least makes it clear what the collection is worth in dollars ahead of negotiations.

· Expect to be asked for detailed checklist with images. Many institutions no longer bring works in on approval or send staff to look. The quality of your documentation can be vital.

· Manage expectations — as you may know more about your collection content than the proposed recipients (the institution).

· Be aware that some regional galleries are less keen on works on paper because each changeover of light sensitive works involves staff costs in preparation and installation compared to paintings left on the walls for long periods or even forever if need be. Check out their collection policy. Hopefully this can be done online (but not always).

· Is the breadth of the type of works in the collection such that the museum is acquiring a significant standing in representation of a period or style that will also attract scholars and requests for loans?

· Is having works for research purposes of value — or not even a consideration?

· Does the collection offer a new perspective on some aspect of visual art?

· Does the collection on offer provide the basis for a future exhibition and scholarly publication?

· Is there a reasonable prospect a large collection will be catalogued and digitized so that the wider public even knows it exists?

· It is heartbreaking to realise that a collection donated is invisible as the museum does not have the collection listed online even without pictures. Indeed, even major art museums seem to be making the ‘collection search’ tabs quite hard to find.

· In your dossier for making an approach, play up any linkages to the location of the museum.

· Being able to anticipate the answers to some of these questions above when making an approach could be mutually helpful. The collector is also the champion of their works and can articulate their importance or tell the story of the collection as part of the approach.

· Be very aware that managing expectations is a delicate operation on both sides. The recipient may be less informed and enthusiastic than you.

· You may want to move everything at once but the recipients have statutory responsibilities and within some institutions the caring for material of little likely use in future is increasingly hard to justify.

· For curators it can be difficult to explain to a stressed family of a deceased artist that all that is being offered can’t be accommodated.

She adds:

To repeat: Each situation varies depending on the value of the collection, the documentation provided — which in each case then needs to be matched against the priorities and requirements of the many regional and larger public collections. All this within the framework of the expectations of all involved. The process of collections being acquired by art museums was always complicated — but I enjoyed it. However I suggest it is not getting any easier for both collectors and the curators. Things have definitely changed.

I have had quite a lot of unexpected contact on this blog from curators as well as people like myself trying to find home for deceased estates or senior artist’s works and archives. It is a worldwide problem as far as I can see but homes need to be found for our heritage.

Photographers’ archives

by Gael Newton

Figure 4.06: Paul Costigan: Gael Newton's illustration for ‘Photographers' Archives’ blog. Screenshot

For many years I have been interested in what happens to photographers’ whole of life archives — only a fraction of which will be accepted for gift or purchase by large public collections.

I felt there might be some sort of future job for graduates as archives advisors and several interns [of the Australian National Gallery] were set projects. The fate and legacy of the archives of my 1970s generation of photographers and collectors is of special interest. To remain posthumously active, photographers’ archives seem to require the dedication of relatives, associates, and friends.

Max Dupain: A large part of the Max Dupain personal negatives was productively managed after his death in 1992, by former associate Jill White, until final transfer to the State Library of New South Wales. White worked with independent art publishers Chapter & Verse on a series of publications of aspects of Dupain’s career. The commercial jobs archive was also active under White and former Dupain Associates partner Eric Saarinen.

Among the interns’ projects I initiated; in the 1990s Annabel Dent interviewed a number of photographers on how they archived their own collections. We found a few, including Sydney photojournalist David Moore, to be exemplary models. At the other end of the scale there were working photographers with a passion for a low-paid arts area they loved, who faced a difficult future. One had not even contact printed their negatives for decades and had them filed in boxes with only an occasional date or place name (the archive was later taken in by a repository). Others felt they could not turn down jobs to take time out for archiving.

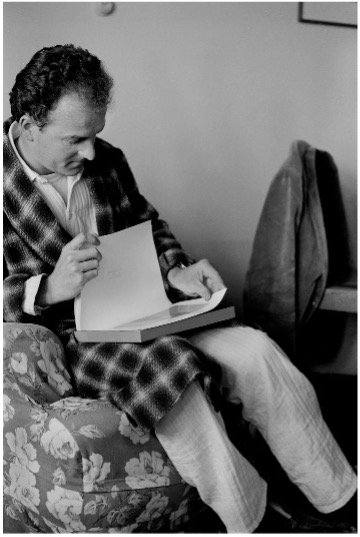

Figure 4.07: John B Turner: David Moore in his studio, Sydney, NSW, 1975. From Photoforum 40, October-November 1977. Our full issue feature section doubled as a catalogue for his 1977 retrospective exhibition at the Auckland City Art Gallery

David Moore was a talented artist but also meticulously organised and a businessman. On one visit to his beautiful home and studio at Blues Point, David unerringly pulled out a folder and opened it at almost the exact page to find an image for me. David had shelves of ring binders recording contact sheets as an index. The negatives could be located as a result. He was ever active planning exhibitions in his lifetime and forward projects for after his death from cancer. His daughter, Lisa - a designer, runs his archive including vintage and posthumous printings and reproductions. It’s a big job running any kind of picture library let alone an artist’s legacy.

Figure 4.08: John B Turner: John Fields sorting a new batch of his prints at home, Mt Eden, Auckland, 1969. (JBT198-16)

Figure 4.09 John B Turner: John Fields, waiting for our meal at Tony's Restaurant, Wellesley Street, Auckland, 27 May 2009. (JBT2009-33088)

John Fields: Former intern Belinda Hungerford, now curator at New England Regional Gallery (NERAM), became expert at staring down large collections of photographic archives of various types. (Website.) Belinda’s recent exhibition Glimpses of New England; John Fields was on the late work of the American-born, New Zealand photographer John Fields, who lived in New England from 1987 until his death in 2013. John worked in a classic American style of richly toned and detailed black and white personal documentary photography. Such a locally focused project is an excellent case of archive harvesting. There isn’t much on the NERAM website but the review is helpful and there is a lot on Fields online. Let us hope his New England archive stays put. [As mentioned earlier, Wellington-based David Langman is also working on the New Zealand component of Fields’ collection.]

Other examples of privately managed photographic estate archives are:

Rennie Ellis: Melbourne photojournalist and lifestyle witness of the 1960s-2000s, Rennie Ellis died in 2003. (Website) His archive has been brilliantly served by his widow Kerrie and former assistant Manuela Furci. Their program of posthumous promotion, printing, publication, and exhibition of Rennie’s work is a model of what can be done. It would have been nice if Rennie had set time in his later years to enjoy some of the recognitions of his life’s work that Kerrie and Manuel have achieved.

Other mid 20th century photographers such as Athol Shmith and Marc Strizic in Melbourne and Jeff Carter in Sydney, were able to energetically exploit the boom of interest in photographic heritage in these years and record their own histories. Museum curators were key factors in these retrieval processes.

Maggie Diaz: The post war American immigrant photographer Maggie Diaz died in Melbourne in 2016 aged 91. Diaz was fortunate that in her 80s she received considerable attention and appreciation of her work came through the single-minded dedication of a young former associate Gwen de Lacy. The Diaz archive has been sold to the State Library of Victoria, but de Lacy continues various printing, publication and managing of the biennial Maggie Diaz Photography Prize for Women founded in 2015.

Peter Dombrovskis. Similarly, Liz Dombrovskis, the widow of famed Tasmanian landscape photographer Peter Dombrovskis, did an extraordinary job in publishing suites of images utilising technology and printing quality not available to her husband. Her sure hand saw a nuanced balance between the calendar images of high key colour and the quieter lyricism of his oeuvre. The archive is now with the National Library [of Australia] who mounted their own exhibition in 2017.

Robert McFarlane. While many senior photographers manage a website, few have been as organised as Adelaide-based photojournalist and writer Robert McFarlane. He is retired from active photographic assignments, but he continues to write reviews and articles. He supplies digital images and exhibition prints from his archive. A local arts award provided precious funds to employ a professional archivist to assist in the cataloguing of Robert’s negatives prior to their placement with the National Library of Australia. A monograph by Wakefield Press SA is in progress. His archive printing rights and future copyright income are an important legacy.

A crucial factor for many artists/photographers is to see a retrospective exhibition and/or publication as part of the safe placement of their work in an archive. Issues of posthumous printing will be a topic for a future posting.

So, what are the options for whole of life photographer archive?

· Preferably the photographer should take steps to provide precious information about the date, place and subject of the material and their hopes for it.

· If there are resources, hire help to mow down what seems to be a mountain of straw waiting to be turned to gold.

· The poorer your metadata on the collection, the more of an onerous task faces a museum or library to the point where more collections are turn down even as a gift.

· Make a checklist of date range, content and format.

· In documentary photography no matter how ‘arty’ even landscape as a subject can matter in telling a narrative of a time and place and attitudes of the day.

· If you can say that certain subjects have been regularly recorded over several decades or concern a particular group or person of note then include those notes.

· Material which in itself might not be the highlight of a career, can make up a significant suite of interest to a repository with an association with that subject.

· Get a few people with different perspectives to look at the list or the images – Who knew there was a museum dedicated to children’s toys?!

· Explore regional galleries, libraries, and historical societies.

· Art museums, however, rarely take whole of life archives and/or negatives.

· Scan lots of images and arrange in related themes or chronologically over the span of years. Prepare easy Dropbox folders to send on spec.

· There are online forms at the major libraries, and you can float the offer of your archive through that portal. Grab an archivist or curator if you know any and ask what they think.

· E-hive can be helpful in finding specialist museums [in Australia].

· As perhaps Museums Aotearoa might prove to be?

Endnote for Part 04: Gael Newton

Figure 4.10: Max Oettli: Tom Hutchins and photography class, Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland, 1971. Students L-R: Liz Davenport, (name?), Nick Empson (standing), Leslie Lash and Gael Newton. Hands-on learning about the Leica rangefinder camera with the lens caps on for protection. Download from Facebook. Courtesy of the photographer

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to Photoforum Director Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, PhotoForum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a former director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

About PhotoForum

PhotoForum Inc. is a New Zealand non-profit incorporated society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression. We maintain a book publication programme, and organise occasional exhibitions, workshops and lectures, and publish independent critical writing, essays, portfolios, news and archival material on this website - PhotoForum Online.

PhotoForum activities are funded by member subscriptions, individual supporter donations and our major sponsors. If you would like to join PhotoForum and receive the subscriber publications and other benefits, go to the Join page. By joining PhotoForum you also support the broader promotion and discussion of New Zealand photography that we have actively pursued since 1974.

If you wish to support the editorial costs of PhotoForum Online, you can become a Press Patron Supporter.

For more on the history of PhotoForum see here.

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of Photoforum Inc.

CONTACT US:

photoforumnz@gmail.com

Photoforum Inc, PO Box 5657, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Directors: Yvonne Shaw and David Cowlard

Consulting Editor: John B Turner: johnbturner2009@gmail.com

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.