NEW ZEALAND’S PHOTO TREASURES HEADING FOR THE TIP? - Part 9

Notes on the collection of photographers’ collections for posterity

A PhotoForum discussion paper by John B Turner

Part 9: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

“Should the value of a collection be decided on how tidy and ready to go to digital it is? I don’t think so! But if our archives had more staff they could obviously spare more time to help photographers and their erstwhile heirs to fill in and tidy up the inevitable loose ends. As it stands, there appears to be an insidious lack of dialogue and action between the creatives and their potential guardian angels working to fulfil the mission of preserving the visual evidence of New Zealand life and culture in all its richness and complexity for future generations.” John B Turner

01: Introduction

02: Te Papa

03: Significance & Archives for Artists

04: Gael Newton: Parting with your art & Photographers’ Archives

05: Auckland Art Gallery & Alexander Turnbull Library

06: Auckland War Memorial Museum & Auckland Libraries

07: Internal Affairs & Heritage Departments

08: Canterbury Museum & Christchurch Art Gallery

09: Collection case studies: Tom Hutchins, Paul Gilbert, Max Oettli & Barry Myers

10: Curating, Barry Clothier Simple Image show & Clothier/Turner 1965 Artides show

Tom Hutchins’ Collection

A sample of Tom Hutchins’ early photographs from Tom Hutchins Images / Turner Collection

Figure 9.01: Tom Hutchins: Composite view of Ballantyne’s fire 1947, widely published under the name of Green & Hahn, the Christchurch company he worked for.

Figure 9.02: Tom Hutchins: Closeup of crowd in Auckland’s Queen Street to welcome the end of World War II, 1947

Figure 9.03: Tom Hutchins: The tanks in Auckland’s Queen Street in the victory celebration led by Montgomery of Alamein, July 1947.

Figure 9.04: Tom Hutchins: ‘Rh factor baby delivered by Caesarian section following successful fetal transfusion treatment by Liley’s technique, National Women’s Hospital circa 1952’. A rare mounted and belatedly signed Hutchins’ print, it appears that the photograph might have been made a decade later, perhaps in 1962 or 1963, when fetal transfusions were novel and given international news coverage. Not surprisingly, due to its intimate nature, it might never have been published in the public or medical press. And if made in the 1960s it might have been inspired by Wayne Miller’s image of the birth of his son, published in Edward Steichen’s Family of Man (1955). This is yet another mystery to solve regarding Tom’s work as a medical activist

Figure 9.05: Tom Hutchins: Proof sheet R25 from Hutchins’ China essay made during his four months visit in the summer of 1956. These images were made in Lanchow, near the Yellow River, in the early morning of Thursday 19 July 1956, when as frame R25/6, indicates, both the foreigner photographer and the old lady with bound feet were equally astonished to see one another in her town. Consequently, this was the only picture of her that he made as a reminder of old China

Figure 9.06: Tom Hutchins: Old woman with bound feet near Lanchow gates, Zhejiang 1956. Note that he tightly cropped the image to remove the man on the bicyle and concentrate full attention on the woman and her bound feet. (RDH_R25-6)

Figure 9.07: Two-page spread from Chinese Photography magazine’s October 2016 22-page portfolio of Tom Hutchins’ China 1956 essay

Figure 9.08: Introduction to Tom Hutchins 9-image inclusion in from China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) from the draft layout of Chinese edition with work by Tom Hutchins and Brian Brake

The issues facing photographers and collecting archives are not always straightforward, as I can verify from my ongoing attempts to place the collection of Tom Hutchins (1921-2007), for which I recently received the intellectual property rights. Finding, the most appropriate and convenient archive for the work can be complicated by collecting focus as well as the location of an archive. And to complicate matters for me, the fate of his collection is partly being delayed by my residence in China and travel restrictions placed to control the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Tom was based in Auckland and earned an international reputation as a Time/Life stringer and member of the Black Star picture agency before joining the University of Auckland as the founding lecturer in photography and film at the Elam School of Fine Arts in 1965. The highlight of his career as a photojournalist was his four-month coverage of China in 1956, one year before Brian Brake (1927-1988) made the first of his several visits to the new People’s Republic of China as a member of the Magnum picture agency.

Wisely, Brian’s huge collection was gifted to Te Papa by his partner Wai-man Raymond (Aman) Lau in 2001, and I had the privilege of studying some of it when writing a chapter on Brian’s early photojournalism for Brian Brake: Lens on the World, (2010) edited by Athol McCredie. Tom and Brian, along with George Silk are the trio of New Zealanders who gained international recognition for their photojournalism of the 1940s to 1960s. Silk photographed China before the Chinese Communist success in winning their civil war, and his collection is safe in the extensive Life magazine archives in the USA.

Te Papa, in Wellington, was thus my first choice for placing Tom’s collection, to make it easier for critical studies of his and Brian’s work in a single location. Undoubtedly, this could disadvantage Auckland-based researchers, but it has its own logic. Te Papa, however, does not appear excited by that prospect, for some of the reasons mentioned in my Art New Zealand (No 160, Summer 2016) article ‘Restoring Photojournalism: Tom Hutchins in China, 1956’; because of the work still to be done to cull and sort his non-China work, mainly put aside while I concentrated on his sorely neglected 1956 China essay. His Time, Life, and Sports Illustrated assignments, including coverage of the Melbourne Olympics in late 1956, and America’s Cup yachting are reasonably well documented, but a lot of his New Zealand photographs are not. Not only do his papers need to be evaluated for their content but also their physical condition, before entering a proper archive. The mix of professional and personal documents relating to his academic as well as photographic careers still needs attention, as do items of camera equipment and some unprocessed films. There is in addition a box of affidavits he collected to document police brutality towards people protesting against the Auckland visit of US Vice President Spiro Agnew in January 1970, and documents of other political events to consider.

Although the content and its historical relevance may differ, it is my impression that the varied nature of the items making up his collection, would be typical of many other photographers. They are not all negatives, slides, prints and documents neatly relating only to exhibitions and publications, and this diversity of subject matter tends to makes it more complicated for any collecting institution to catalogue.

To make matters worse, Tom’s 65 year old 120mm format China negatives stored in Auckland have started to deteriorate before they can all be digitised. The good news, however, is that 1,400 or more of Tom’s 6,000 plus 1956 China images are now receiving widespread recognition in China via the country’s largest picture agency, the Visual China Group, and have been added to the vast international Getty Pictures’ offerings. His work is justifiably being featured in anthologies and is gathering a larger international audience in the process. But the ultimate fate of his collection which I have been trying to look after since 1989 continues in the balance among non-competing and at times seemingly uninterested specialists.

Ultimately, by not respecting his (impressive) legacy as a photographer, Tom proved to be his own worst enemy and a warning to all photographers who would like to have their work evaluated by social and cultural history specialists before it is consigned to the dustbin of history by default.

I have focused on the reconstruction of Tom Hutchins photographs of 1956 China in particular because it is not just a major and unique photo essay, but also the single most important body of work he made in his lifetime. It did not help that he had given up on his original idea of making a book to share what he saw. Nor that the New Zealand press in the 1950s and 1960s already had a strong anti-China bias. Another impediment for Tom, once he returned to New Zealand was the lack of news from Chinese sources and the Western bias of the mainstream press. He was upset that the promise of greater personal freedom of expression for the Chinese people was being stifled by new less liberal political developments and news of disastrous social experiments that undermined the most heartening evidence of improving conditions that he had witnessed. Imagining the worst, he worried for years about what had happened to his favourite interpreter, Jia Aimei, with whom he eventually made contact with great relief 38 years later in 1994.

Seemingly disinterested at first, he occasionally became excited at times by the progress being made on ordering his damaged papers and reprinting his work after his original prints were mostly destroyed by mould and snails because they were foolishly stored under his house.

Since Tom died two months before my first visit to drum up interest in China in May 2007, it’s also been a roller-coaster ride because his trustees forbade me from exhibiting or publishing his work in China for fear that they would be pirated. They eventually relented, but that’s another story.

The results of 30 years preparatory work have started to come in in rapid succession, very much aided by digitisation and the internet. Both Tom and Brian Brake were represented among the 120 included in China through the lens of foreign photographers, published by China’s Zhang Xin in 2020. An English language edition is due to follow. It’s rewarding to see images by these New Zealanders alongside many outstanding practitioners including the likes of Jack Birns, Carl Mydans, Bruno Barbey, Koichi Sado, Edward Burtynsky, Nadiv Kander, Robert van der Hilst and others from a later generation in this handsome upbeat collection from the past 70 years. Just as it seems inexplicable and inexcusable that some of the most important trailblazers, including Magnum’s Henri Cartier-Bresson, Marc Riboud, and Eve Arnold, were not included.

I was the voluntary projects manager for Tom Hutchins Images Ltd, the company he and Rob, his eldest son, set up in 2000 with a Dunedin lawyer. But sadly, Rob unexpectedly died in 2018, and a close friend of his replaced him as a main trustee, until they decided to close the company and to my surprise, reassign Tom's intellectual property rights (copyright) to me in December 2020. A change which gives me even greater responsibility for the future of his collection and informs my growing concern about the state of collecting significant photographer’s archives in New Zealand, China, and around the world.

But there is always hope, and although my efforts were too slow for Tom or Rob to see the new publications, the National Museum of China, which I had first approached in 2016, purchased 28 of Tom’s prints in February 2022. Combined with the increased internet spread via VCG and Getty Pictures monetisation, my dreams for Tom’s work could bring some financial reimbursement as well (Sales up until June 2023 have been slow and small, incidentally, but simply searching online for “Tom Hutchins China 1956” brings a flood of his images from numerous sources, including unauthorised but competent digital colourisation).

The Covid-19 pandemic has not helped me find a safe haven for Tom’s collection, nor for my own books, prints and papers which are still in an Auckland lockup waiting to be sorted and dispersed. My initial hope was that Te Papa would take Tom’s collection to add to Brian Brake’s later and extensive China coverage. My second choice was the Alexander Turnbull Library, but with staff changes there and my limited time in Auckland, its proven impossible to find a mutually suitable time for them to inspect his collection. And although too scared to risk bringing Tom’s negatives to China to work on, I have contemplated the idea of selling them to a Chinese museum if New Zealand doesn’t care enough.

The evidence that our chief archival depositories are more and more reluctant to accept whole collections like they used to, and now fuss over whether or not to adopt the work of an eminent New Zealand photojournalist, filmmaker, teacher, critic and social activist who foolishly left his collection in a bit of a mess, is chastening, to say the least.

Expecting donors or sellers to provide an inventory of the collection before an archive will consider accepting it seems a reasonable expectation. But delays in safely rehousing an archive always risk the tragic fate of Tom Shanahan’s collection, destroyed in a lockup fire while his family were trying to catalogue it to abide by new library rules for acquisition.

Should the value of a collection be decided on how tidy and ready to go to digital it is? I don’t think so! But if our archives had more staff they could obviously spare more time to help photographers and their erstwhile heirs to fill in and tidy up the inevitable loose ends. As it stands, there appears to be an insidious lack of dialogue and action between the creatives and their potential guardian angels working to fulfil the mission of preserving the visual evidence of New Zealand life and culture in all its richness and complexity for future generations.

Paul C Gilbert’s Collection

A sample of images from Paul C Gilbert’s Collection

Figure 9.09: Paul C Gilbert: Screenshot from Photoforum’s website review of Road People of Aotearoa (2020) with caption: Dale Whitcomb and Trevor and Rangi McGlinchey’s trucks, 309 Road, Coromandel, 1979

Figure 9.10: Screenshot from Paul Gilbert’s Aquapx website, 2014. As valuable as they can be, there is a serious issue about what can be done to archive a significant online collection when its creator dies, the web company’s rules change, or as likely, there is nobody to continue it?

Figure 9.11: Paul Gilbert: Untitled, Auckland, 2012. Turner collection

Figure 9.12: Two pages from Paul Gilbert's early book dummy for Road People of Aotearoa. Gilbert collection

Figure 9.13: Paul C Gilbert: John Tucker driving, n.d. Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

Figure 9.14: Paul C Gilbert: Robyn’s house truck, the first built by John Tucker, after the 1982 Sweetwaters Festival. From Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

Figure 9.15: Paul C Gilbert: Dave Sheridan’s fire eating act, Road Show Fayre, Nambassa, 1978. From Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

Figure 9.16: Paul C Gilbert: Neelie (the dog), David Sheridan, Paul the ‘Grey Wizard’ (with hat) and Claire Honeyman in front of the Wizard’s truck, Aratiatia, 1984. From Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

Figure 9.17: Paul C Gilbert: Fern Flat camp, Northland, 1978/79. From Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

Figure 9.18: Paul C Gilbert: The road people who visited the Mahanaland community at Coromandel after the final Nambassa Festival of 1981. From Road People of Aotearoa, 1978-1984. Gilbert Collection

The early death of Paul Gilbert (1954-2019) in August 2019, and Haruhiko Sameshima’s determination to publish Paul’s Road People of Aotearoa photo essay were important prompts for me to put other projects aside and look more deeply into the issue of photographers and their collections.[i]

Paul was a valued friend and colleague who had taught with me, Megan Jenkinson (and also Haru) at the Elam School of Fine Arts at the University of Auckland between 1995 until the end of 2008. Despite being an outstanding art school technical instructor, University politics shamefully forced him out of his job. An alternative lifestyler by choice, who valued people and cherished personal projects (photography and sailing) before money, he found himself facing unemployment and ageism in a workplace that rejected the depths of his experience, expertise and enthusiasm. Exacerbated by financial problems his health gradually deteriorated and he died from cancer just four months before his first pension payment and a guaranteed income was due.

Paul was highly skilled as a professional photographer in technical areas, as a marine specialist, and was a witty and often sardonic chronicler of people and society in his personal photography. He left behind a mix of well documented and organised pictures along with thousands of unidentified negatives and transparencies made over half a century - that To Do backlog many photographers imagine attending to when they retire but don’t enjoy as much as piling on new work.

Paul was too ill to complete his most cherished book project, Road People of Aotearoa, but he died knowing that his late 1970s to mid-1980s photo essay on the alternative house-truck and traveling circus movement would be completed and published with the help of his family, friends, and admirers. The book was published by Haruhiko Sameshima’s Rim Books in Auckland in October 2021.

Figure 9.19: Mac Miller: Photographer at Auckland Zoo, 1970. Courtesy of Mac Miller. The photographers didn’t know each other but the young photographer in the picture was Paul Gilbert who at 16 was freelancing as a street photographer.

What will eventually happen to his collection, which is in the care of his siblings and children, is not known, but they respect its intrinsic cultural and historical value and have committed to do what they can to get it into shape as an enticing package for a suitable archive. Fortunately, Linda Gilbert, Paul’s younger sister is an artist in her own right and with her brother Bruce, also learned to appreciate art by their mother’s example. Which means that they should be able to work out which of Paul’s photographs should go into the art basket and which have value as historical documents in the first place: that tricky task too often left to the librarians and archivists by default.

As well as his extensive and respected website of New Zealand maritime photographs ‘Aquapx: The art of marine photography’ there are a few Blurb books made by Paul to guide his heirs. Personal books that were well worth doing but never money spinners in his hours of need, unfortunately.

Haru Sameshima’s admirable Road People of Aotearoa essay outlined the process involved in posthumously selecting and identifying images from the unannotated collection of around 3,500 photographs that Paul had made over the period of roughly 8 years from 1977 to 1984, in order to, with some help from Megan Jenkinson and myself, finally edit and sequence the work for the book.

Although it created an awkward aside - which we discussed editing out - I felt compelled in my essay for the book to warn other photographers of the dangers of procrastination by drawing attention to the fact that despite his best intentions, and the high level of art and historical value of his work, Paul was typical of most of the photographers I know who fail to consistently document and file their work when the specifics are fresh and clear.

Having spent many years bringing Tom Hutchins’s China 1956 essay back to life, I wrote with some urgency:

‘Photographers need to pay more attention to editing and cataloguing their work and heritage as they create it. It makes no sense to leave these tasks to somebody else when the link to the specific meaning and value to its author has been cut off. Life gets in the way, of course, and art tends to thrive on ambiguity, but leaving cherished images without an anchor invites its own peril. Our most active public collecting institutions are starting to run out of space for physical storage and are refusing to continue to take on this task, no matter how significant it’s author or content may be considered. It’s not an easy task, but if we want our work to be valued as visual evidence and art, the first step is to ensure that we photographers take personal responsibility for the crucial task of creating archives of our own work…. ‘

Typical of so many prolific photographers, Paul could never catch up with the task and never got around to clearly documenting all of his photographs as to subject matter and dates. His Road People images were partially organised – clumped together as to their intended documentary purpose – but less individually than his maritime pictures, for which he created his own picture library. Like most of the independent photographers I know (including myself), who make pictures for themselves to scratch an artistic itch, rather than for commercial use, I’m sure Paul had the images for this book precisely catalogued in his imagination before his time ran out.

As a photographer and sometimes curator I empathise with the demands on dedicated picture librarians and curators whose job it is to sort the wheat from the chaff for the common good. In my experience they are less handicapped by either the egos, nostalgia, or fundamental uncertainties that prevent photographers from wisely culling their shots. Or to the contrary, those who ruthlessly destroy their early and secondary work in the belief that it is the best way to protect their reputation as artists. It should be understood that their perceived less-than-best images not only demonstrate the struggle and context for their expressive “successes” and practice, but likely have useful social-historical value as well.

I know that because I’ve entered my 79th year and feel the responsibility of wanting to explain the context, public and private, in which my favourite pictures were made, and I can’t trust anybody else either to perceive, care or value them as I do, warts and all.

[i] Road People of Aotearoa: Images of house-truck journeys 1978-1984, Photographs by Paul C Gilbert, with foreword by Michael Colonna and essays by Haruhiko Sameshima and John B Turner. Rim Books, Auckland 2021.

Max Oettli’s Collection: going digital

Figure 9.20: Max Oettli: Matchless 350, Waikato, 1966. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 9.21: Max Oettli: West Wind Coffee Bar, 1968. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 9.22: Max Oettli: Curb, Queen Street-Wellesley Street, Auckland, 1969. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 9.23: Max Oettli: Troops return (2), 1973. Auckland Art Gallery Toi o Tamaki, gift of Max Oettli, through the Auckland Art Gallery Foundation, 2018. Courtesy of the Auckland Art Gallery

Figures 9.24: Max Oettli: Negative and positive impressions of his Auckland 1972 photography of a girl licking an escalator. Illustrations from ‘Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography Max Oettli. Turnbull Library Review, Volume 53, 2021

Figure 9.25: ‘The negative needed considerable restoration work. Photographer: Max Oettli (ATL ref. PADL-000106-29)’. Illustration from ‘Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography Max Oettli. Turnbull Library Review, Volume 53, 2021

Figure 9.26: Mark Beatty, ATL: Max Oettli sorting his negatives for digitization at the Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, 2020. Courtesy ATL Imaging Services. Illustration from ‘Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography Max Oettli. Turnbull Library Review, Volume 53, 2021

Figure 9.27: Max Oettli: Family, Auckland, 1972. Courtesy of the photographer

Figure 9.28: Paul Chapman, AAG: Installation detail of the exhibition ‘Max Oettli: Visible Evidence, Photographs 1965-1975’curated by Ron Brownson, shown from 18 December 2021 to 12 June 2022 at the Auckland Art Gallery

Figure 9.29: Dean Purcell, NZ Herald: “The boy in the picture, that’s definitely me” – John Kearns. NZH 16 February 2022.

Born in Switzerland in 1947 Max Oettli emigrated to New Zealand with his family in 1956. He grew up in Hamilton and studied at the University of Auckland and after returning to Switzerland in 1976, at Geneva University, and subsequently taught architectural photography at Geneva Polytech and also at the Federal Polytech in Lausanne. He was the first full-time Technical Instructor at the Elam School of Fine Arts from 1970-1975 and in 2007 returned to New Zealand to take up the position of Principal Lecturer in Photography at the Dunedin School of Art until 2012.[i] Retired now, he has been living between Wellington and Geneva and spending a great deal of time cataloguing and sorting his photographs for dispersing in two countries.

A multilingual photographer and writer, Oettli (pronounced “Urt-lee”) did not make proof sheets of his analogue photographs. Like many press photographers, for whom speed of getting prints to their editor was the priority, he learned to read negatives when he was a cadet photographer at the Waikato Times in the late 1960s. Instead of making proof sheets for filing, he relied on intermediate work prints from which to re-edit his images and guide subsequent printing for exhibition or publication. For him, as he recently wrote in relation to preparing a digital spreadsheet of his images: ‘Useful though the spreadsheet was, I have an instinctive need to actually confront the pictures I am consulting. I need to be able to flick through them [on screen] and choose the ones I feel best meet the criteria I am engaging with. Call it instant curating I suppose, and [the habit of] years of thumbing through bundles of work prints.’

About his filing system, he wrote:

‘The negatives were mostly in individual sleeves stocked in kauri boxes, some ex-library, some made by me. They had a system of registration using a letter and a number and occasionally some details like names or dates were scrawled on them. The boxes contained between 20 and 30 films, so possibly 100-150 sleeves, and usually represented a year’s work. Some of the negatives, shot on old cinema film stock, had no reliable frame numbers.’

Altogether, he notes, there are now 14,037 digital files and 296 folders, totalling about 14 Gb, of his early New Zealand photographs in the Turnbull Library.

Better late than never! Or ‘About time, about time...’ as Max headed his timely article in the Turnbull Library Record, ‘Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography’ (2021).[ii]

Even if we weren’t old friends and former colleagues who first met in 1970, and if he hadn’t inspired me to be more spontaneous with my own 35mm camera work, I’ve seen enough brilliant images of his to click “Follow” in my brain and be concerned that his work, or at least the best of it, is appropriately preserved for posterity. And not just his New Zealand work which means more to parochial New Zealand and less to parochial Swiss citizens and vice versa.

Fortunately, most of Max’s other photographs are stored in the cool room of the Geneva State Archive: ‘Here in the city republic my negatives and transparencies (some 30,000, dating from 1976–2007) have ended up in the state archive in a cool room, still in their original packing.’

I have scanned perhaps 20% of them, mainly aerial photographs from the late 1970s to the first few years of the 21st century. These are all on DVD and hard drives in various of Geneva’s suburban administrations, and in a greater quantity at the Planning and Topographical Service. These interesting documents gather historical value as the new century advances and the region becomes an immense work site, as all cities are. The state authorities can’t afford do the rest of the scanning for now, apparently, but I’ll keep pestering them.

Figure 9.30: Online catalogue details for Max Oettli’s collection in the NZ National Library

Figure 9.31 (a)

Figure 9.31 (b)

Figure 9.31 (c)

Figures 9.31 (a), (b) and (c): An online catalogue search comes up with confusing identification due to images grouped under general categories rather than individually for Max Oettli’s collection in the NZ National Library.

Figure 9.32: The grouping of Max Oettli’s images searched in the NZ National Library’s online catalogue is confusing due to the grouping of images which makes it difficult to identify individual images. (See figure 23 above) . Screenshot. Courtesy of NZ National Library

One of the great advantages of digital imaging is how accurately the optical and aesthetic quality of original photographs can be so convincingly duplicated and presented on the interface of our computer displays. That magic dissipates, however, when the image is digitally projected, shrunk or overblown on the monitor of a computer or other digital screen. But with appropriate technical skill and sensitivity, it is now possible to replicate any photographic image almost perfectly in a fine digital or hybrid print. In that sense, they can be seen to equal the distinct beauty of the early photogravure printing process for reproducing “black and white” prints (which actually come in many nuanced colours) and the layered multi-colour glory of the best of offset printing today.

For those not familiar with seeing how well photogravure could represent the look of a photographic print I recommend studying Ans Westra’s landmark Maori (Reeds, 1965) as a fine example of the once-dominant process now superseded by digital scanning and offset printing. Maori was designed by Ans, who provided the Japanese printer with exact-sized prints, and polished for printing by Gordon Walters (now known as a leading NZ painter). It is pioneering book/artwork/photobook in its own right, for reasons of its content and form, and given that the digital toolbox is infinitely more sophisticated than the hidden handwork that lifted photogravure to its heights, it would be interesting to see Westra’s original Maori prints revisited as digital copies to compare and contrast how faithfully each method actually conveys the distinctive qualities of a particular gelatin silver print. (Coincidentally, the Turnbull Library has had a long-time continuing collaboration with Westra to preserve and share her work, which along with Oettli’s was used to stimulate the imaginations of secondary school pupils in Peter Smart’s influential Let’s Learn English textbooks of the early 1970s).

The current protest over the New Zealand National Library removing actual books from their collection because they are available in digital form, demonstrates the positive convenience of speedy access and unlimited sharing of their primary content, while totally ignoring the book as an object and even artwork in its own right. Their focus on culling books not made in, by or about New Zealand’s South Pacific patch is equally unbalanced because, as we artistic types know, our ideas and inspiration come from all over the world on every unpredictable subject and source.

In either case, when it comes to technological changes the critical choice is between different and better, and different and worse.

If analogue printing is no longer an option, instead of making gold-toned, selenium, or platinum prints to last as long as possible, it still makes sense to use the traditional ink on paper solution for communication and relative permanence. Because traditions die hard, it is interesting to and note the remarkably speedy acceptance with which digital prints by contemporary practitioners have been received in the conservative and traditionally sniffy art market. Especially when one remembers the reaction to the introduction of resin-coated printing papers , which were designed to save the silver, chemicals and water needed to make a fibre-based print with its beloved characteristic full tonal scale , that the plastic-based paper failed to match.

Once again, this raises the question of whether pre-”born digital’” analogue practitioners and hybrids like Max Oettli and our generation will be represented by the minority (a tiny number of hard-won prints) or majority (digital replicas eked from negative and positive material templates) in the long run? In either case, I have no doubt, from what I saw in Wellington when we met up in early 2020, that the envisioned monograph drawn from his own selection of 700 early photographs would be a significant contribution to the history of New Zealand photography alone, while his digital records will be seen as valuable addenda. [iii]

This is not the first such collaboration between a photographer and library, of course, and it should not be the last, because it demonstrates how easily the potential use-value of specific images can be overlooked in the photographer’s necessarily tight selection of favourite pictures for exhibition or publication in an art or quasi-art context. It demonstrates not only how history and art history are close neighbors on a strip of film, but how irresponsible it is to neglect careful evaluation of a photographer’s negatives before irreversible decisions are made about their destruction. Unfortunately, this kind of collaboration can seldom be contemplated let alone regularly actioned, unless a collecting institution is adequately staffed and resourced.

One outcome of the Oettli Project is evident in the palpable enthusiasm shown by the library staff who worked with him during the 18 months he spent doing most of the necessary donkey work under their expert guidance. A modest payment was made for each scan, and oddly, I think, that work was done with his own scanning equipment. So, I trust that is not a prerequisite to discourage other living practitioners from seeking the help of a library to cull their print collections and supervise the making of their own born-again digital positives.

Absolutely, Positively, to borrow the Wellington city slogan, the Turnbull Library is celebrating its part by adding Max’s work to its collection and making it available online in double quick time. The online results are not perfect, but what I imagine Max might describe as “a trifle clunky”, due to the design which links images in six image film strips (faithfully echoing his idiosyncratic early filing system) that often frustrates the search for individual captions.

There are other issues of quality control to consider: with one to do with the lack of dodging of some images, especially from underexposed or over-contrasty negatives rendered virtually useless without tonal adjustments in key areas. The needed “spotting” of dust marks seems also to have been postponed in the forlorn hope that a purchaser might or can do it before it is published or presented in the raw. I expect however, that many people won’t know the pros and cons of removing what is the visual equivalent to the screech of static on a soothing music track; or like finding accidental ink marks, which printers call “hickies”, on what should be the clean page of a book. The Born Digital generation is largely ignorant of these seemingly esoteric technical/aesthetic issues designed to complete the illusion (when wanted) of a photograph seamlessly substituting for “the thing itself”, without which they can easily be as off-putting as a fly speck on a drinking cup.

Max admits that he did not have the time, and arguably the skill to make his 16,000 scans perfect:

“I corrected the levels to come up with a reasonable picture quality and occasionally did a little minimal spotting of scratches and other obvious faults (on the assumption that if a photo was to be published a professional retoucher would do a far better job)”.[iv]

Unfortunately, because our National Library doesn’t seem to employ staff with editorial and proofreading skills, there are a pathetic number of “typos” and ignorant mistaken descriptions to laugh or despair about, such as identifying Ans Westra’s signature Rolleiflex camera as a “Roloflex”, and the nonsensical catalogue descriptions I found in their documentation of Barry Clothier’s collection described in Part 10 of this blog series. Seriously, there is something wrong if we don’t expect higher language and subject skills to accompany the digital deluge. Accepting Max Oettli’s often facetious personal shorthand at face value in lieu of legible and factual captions, while provably better than nothing, cries out for competent editorial supervision and proofreading from a national library.

Nevertheless, thereis at work a serious effort to demystify the practical processes employed by an independent photographer to turn his negatives into positives with as little curatorial interference as possible.

‘About time, about time…’, indeed, these are the words of an older Oettli who, in 1974, as the first President of PhotoForum Inc, dedicated his cheeky President’s Report to ‘oblivion and future generations of hungry silverfish’.[v]

Nearly 50 years later, inevitably, it’s our generation’s turn to find that avoiding oblivion and the silverfish is a trifle more real. New sponsorship and income streams are needed to boost the tiny, saturated marketplace for fine photography. Photographers not only have to vie for the attention of art galleries and collectors but also libraries and museums to save at least some of their work. Self-publishing, rather than being a derided niche activity is becoming the only way for some of the most significant work done to reach the public, let alone provide any income. Learning to blog and actually sell work via the Internet is a skill to be taken more seriously and learning to digitally scan images to a professional level is becoming as necessary as typing on a keyboard, emailing and using a cell phone. Although we may have spent most of our lives donating our photographs to one cause or another, because subsidising the paid work of others, such as professional editors or curators, was the thing to do (and there is usually some joy in the giving), we have perhaps reached the point when accomplished photographers really must develop the skills to compete as a professional benefactor in the public arena to claim their legacy in trickle-up economics.

While we expect art curators to be picky about what their institution acquires - even when works are donated or subsidized to fit their budget - and practitioners feel rewarded by the inclusion and list it on their curriculum vitae, the exchange is not necessarily fair. I don’t know if it was an either/or situation when Max Oettli chose to donate around 200 of his rare vintage prints to the Auckland Art Gallery, from which the exhibition of 75 works, ‘Max Oettli: Visible Evidence, Photographs 1965-1975’, was chosen by the late Ron Brownson, one of New Zealand’s most astute curators and supporters of photography.[vi] But I for one expected the gallery to provide a more substantial critical survey of Max’s early work. It also seemed remiss of the Gallery not to produce even a modest catalogue, (or video for that matter) as a quid pro quo for a very generous donation.

Subsequently, the opportunity to properly acknowledge Oettli’s contribution to contemporary New Zealand photography was lost, as was the opportunity for an Auckland showing of Te Papa’s survey The New Photography…. which showed Oettli’s work in context with his peers , because our national museum decided not to tour it. [vii] (See Part I of this report for details about that exhibition). Te Papa, incidentally, have 59 vintage Oettli prints to date.

The National Library’s Oettli project was first introduced at a National Digital Forum held at Te Papa on 21 November 2018 as ‘Series N for Nikon: A case study of collaborative digitisation and description….’

Since February 2017 staff at the Alexander Turnbull Library have been collaborating with photographer Max Oettli on a project to digitise and describe over 10,000 images from his archive of 35mm negative film strips.

While in many ways this project was embedded in existing Library practices, it was also wonderfully unusual: Oettli himself joined the Library as the technician to scan material and capture descriptive information. Library staff provided technical and methodological guidance, metadata enhancement, and administered the wider curatorial, collection management, and digitisation ecosystem.

What did we learn from this distinctive model of collaborative digitisation and description?

[Turnbull Library Digital Archivist] Flora Feltham will discuss this project and its details: how we developed new procedures for bulk description and digital transfers, how we dealt with unexpected technical issues, and what we might have done differently if only we were clairvoyant. Most importantly, this presentation will unpack all the quick-thinking and creative troubleshooting – as well as the essential ad-hoc decisions – made by everyone involved: Max Oettli, the Digital Archivists, and the Photographic Archive Curator.

In the spirit of collaboration and transparency, this talk will also share Max Oettli’s own reflections on the process: what better way to discuss effective collaboration than to ask the people you join forces with.

This Pecha Kucha approach to recognising individual photographers is much preferred to the demeaning old practice of having one’s work credited solely to a Library, and I should note, as the owner of Max’s old Leica M2, that the series should have been headed ‘L for Leica….’

As a later promotional blog suggests, library staff appreciated the opportunity to interact with the author of the photographs. Digital archivist Flora Feltham wrote:

‘Have you ever wanted to know what Grafton Cemetery looked like before the Southern Motorway was developed? Or what people wore to a John Mayall concert in 1973? Or if there was ever a giant replica of Michelangelo's David in an Auckland department store? Well, look no further….’

‘As one of the Library’s Digital Archivists’ ‘I worked with Oettli on creating metadata for the hard copy negatives and the digitised frames. After scanning was complete, I prepared the digital portion of the collection for long-term preservation, and transferred files to the National Digital Heritage Archive (NDHA) where they are now available. Working on such wonderful material – and being able to discuss it with Oettli himself – has been a definite highlight for me in 2018.’

Photographers need to pay attention to the technical requirements of digital scanning, so Max’s description in the Turnbull Library Review might help others, even though so many libraries deliberately present lower resolution and even rough scans for searching, with the promise of higher quality and better finished scans being available for purchase. The fear of pirating and copyright infringement along with digital space saving and speed of delivery are the usual understandable reasons for such caution, but do nothing to enhance the viewing experience, and are likely to delay or postpone the most meticulous research.

Max wrote:

Following Claire Viskovich’s technical sheet for imaging at the Turnbull Library, and slightly surpassing it, I scanned at a resolution of 3,200 dpi greyscale (4,400 x 2,200 bits, 23 MB per picture) with a 16-bit depth, 6.6 cm at 2,000 (4,500 x 4,500, roughly 32 MB), and 4.5 cm at 1,000 dpi (giving us 4,300 x 3,200 bits, or 27 MB). These files are solid enough for prints up to A1 size, which is 84 cm on the long side. I have had a couple made by Kevin Church (an old student of mine) at Optimix in Titirangi, and am very happy with the result.

For colour images (there are only a handful), I scanned at the same resolution and at 32-bit depth. They are generally not as sharp, given the three-layer structure of colour films. I usually do a rudimentary correction of the colours using Photoshop’s auto-colour option, and keep the original uncorrected version as well. Colour files scanned from 35 mm negatives weigh in at about 33 MB.

He used his own Epson V700 scanner coupled with an elderly PC and an old (CS3) version of Adobe Photoshop and finally made reductions of all of his files to jpgs of about 1 Mb to allow for a more manageable method of handling them…. (Additional details and comments are given in his Turnbull Library Review article.)

While this case study of digital scanning provides useful information for photographers and library specialists, it is increasingly doubtful, that many archives, if any, could presently cope with any increase in the number of photographers desperate for their services. And as always, the challenge is to do a better job next time.

[i] See Postcards from Dunedin: Photographer Max Oettli on documenting New Zealand in the 1960s and 70s https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WwrL_95G3z0 premiered on 12 June 2020.

[ii] Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography Max Oettli. Turnbull Library Review, Volume 53, 2021, pp 25-37.

[iii] See Max Oettli's digitised collection, Photographs of New Zealand scenes, Ref: PA-Group-00002.] and The Days of our (digital) lives | National Library of New Zealand

[iv] Quand J’étais photographe: Archiving a life in photography Max Oettli. Turnbull Library Review, Volume 53, 2021, p30.

[v] See Erika Wolf’s ‘Interview with the President….’, in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, clusters, and debate in New Zealand (Rim Books, 2014).

[vi] The exhibition ‘Max Oettli: Visible Evidence, Photographs 1965-1975’ is scheduled to run from 18 December 2021 to 12 June 2022 at the Auckland Art Gallery. The title ‘Visible Evidence’ was that of Oettli’s first exhibition, held in 1970 at the Wynyard Tavern coffee bar on Auckland’s Symonds Steet, close to the Elam School of Fine Arts.

[vii] See Part I of this report for details about that survey exhibition.

Barry Myers

The future of unique long-term New Zealand photo essays by a visiting US photographer hangs in the balance

Figure 9.33: John B Turner: Barry Myers working on his Newmarket essay, Auckland, 1982. Negative in Myers collection because Turner took the photograph on Myers’ camera.

Barry Myers was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania in 1951 and grew up in the city, attending public schools. He has a BSc in Photography from the Rochester Institute of Technology (1972) and a M.Ed in Educational Psychology from the University of Rochester (1975).

After graduate school he worked as a freelance writer for special projects at Mister Rogers' Neighborhood, a half-hour educational children's television series which lead to him doing a documentary photo essay on children in Pittsburgh under the advisory of child psychologist Margaret McFarland, photographer Harold Corsini, and Fred Rogers the TV host. Barry’s part-time photography project enabled him to establish his own studio and resulted in his ‘Growing Up in Pittsburgh, 1975-1980’ essay.

Primarily working as a commercial photographer in Pittsburgh and in Washington DC, the projects that are most important to him are the ones he did for himself. He got restless and wanted to explore life in other countries, so after earning enough money, he would have bouts of living abroad for a year or two and find things to photograph that interested him.

His self-initiated projects included ‘Locri and Antonimina -1987-88’, for which he received a Fulbright research grant to document daily life in two towns in Calabria, Italy and lived there for 13 months. He lived in London for a year and traveled to many places in the UK during 1980-81.

On his first visit to New Zealand in 1972, he started his ‘Fisherman of Ngunguru, 1972-2013’ essay which is now ready to publish (see Figure 9.38). His 40-year longitudinal documentary of a Māori fisherman and his descendants continued when he lived in New Zealand again in 1981-82, 2012-13, and on a shorter visit in 2005.

With the express purpose of documenting daily life in a small New Zealand town, he started his full-time year-long ‘Newmarket’ Auckland documentary project in 1981. And returned for 13 months in 2012-13, to photograph the town to eventually compare and contrast the changes 30 years on.

Back in the USA, over a four-year period he documented the famous Del Mar horse racing track in Southern California, which was published as Del Mar at 75, Where the Turf Meets the Surf, with text by Jay Privman, in 2012. In 2015 his book Iron Sharpens Iron was published, depicting a full season of Pittsburgh's Central Catholic High School's Vikings football team from their first practices through to the championship game. High School Musicals, published in 2018 was a study of two Pittsburgh high school musical productions: Mary Poppins by Central Catholic High School and Drood by Woodland Hills, from the auditions to their resulting performances.

Now retired, Myers has returned to his New Zealand work with the intention of exhibiting and publishing it to complete the circle, which also involves finding a suitable home for the greater bodies of the work from analogue negatives and prints to digital files.

The Auckland War Memorial Museum already has a small sampling of his Newmarket prints from an early exhibition and clearly would be the most appropriate archive for both essays. Myers is seeking a publisher, but the ultimate fate of both essays in totality - negatives, prints, digital files and all, is uncertain and sponsors are sought in the hope of saving them. Obviously, they should come to New Zealand, but once again, it looks like the vision and determination of the kind needed to attract sponsors during this window of opportunity, when good will is still alive, is seriously lacking.

I hope it doesn’t come to that, but I am reminded of the tragic case of the pioneer colonial photographer, D L Mundy, in poverty at end of his life after trying for years to get recognition and support from the NZ Colonial government to save his hard-won country-wide documentation in the wet-plate era of the 1860s and 1870s. He knew that his work had helped to attract immigrants, but nobody cared, and it appears that his negatives were eventually destroyed.

And closer to this time, Myers’ situation seems close to that of John Fields, the prolific and influential US-born photographer whose collection – a decade of outstanding photographs - went to Australia with him in 1976 without any NZ archive attempting to acquire his work for posterity since.

A selection of 1981 photographs from Barry Myers’ ‘Newmarket’ essay, courtesy of the photographer

Figure 9.34: Barry Myers: Sunbeam Fish Shop, Newmarket, 21 August 1981. The woman in the photograph is a customer being helped by the son of the owner of the Sunbeam Fish Shop, 137 Broadway. Besides offering fresh fish, the shop had a thriving business selling fish and chips

Figure 9.35: Barry Myers: Newmarket Manual Training School, June 1981. The boys in the photograph were taking a woodworking class at the school on Seccombes Road, Epsom. Students from around the Auckland area were bused to the school one day a week: woodworking and perhaps other classes for boys, and home economics/cooking for girls. I returned to do more work at the school in August that year

Figure 9.36: Barry Myers: Abel's Payday, Newmarket, September 1981. The man walking out the door has just gotten his pay envelope for the week at Abel’s Ltd. The other men queue to get their wages which were paid in cash. Abel’s manufactured margarine and other largely coconut oil-based products at their plant on Carlton Gore Road, owned by Mr. Stuart Abel. I shot there on two days, September 9, and on a later day that month.

Figure 9.37: Barry Myers: Charles Lees Brass Manufacturing, Newmarket, July 1981. The men in the photograph are pouring hot metal into a mold. The foundry on Kent Street produced brass parts, mainly for the plumbing industry. The owner of the company was Bob Lees.

For more of Myers’ Newmarket images see Part 6

Barry Myers’ Fisherman of Ngunguru. A book about a New Zealand fisherman and his descendants 1972-2005 and 2012

Figure 9.38: Barry Myers: Three two-page spreads from the design of ‘Fisherman of Ngunguru’, his book about a New Zealand Māori fisherman and his descendants photographed over several decades. Courtesy of Barry Myers

These illustrations are from three separate two-page spreads from Barry Myers’ unpublished Fisherman of Ngunguru book from his extended essay over a 30-year period and show Conrad as a teenager (right top, second spread) and as an adult with his father (below right) who shared a difficult relationship.

Myers is typical of many independent documentary photographers who work on personal projects without any guarantee that they will be exhibited or published – especially in the way they consider best represents their experience of the subject matter and how it should be presented without compromise. They consequently end up with hundreds or thousands of perfectly useful images of historical significance that will never be seen unless they are adopted by a library. This is the situation of many of New Zealand’s finest photographers and is complicated when the work covers different countries and subject matter outside of the understandably parochial interests of most public collecting institutions.

One can’t expect Pittsburgh libraries to desire documentary essays on New Zealand any more than the reverse, unless the heirs of W Eugene Smith admired our country so much that they would offer Smith’s landmark 1955–1957 Pittsburgh essay of more than 10,000 photographs and negatives to a New Zealand art gallery on terms sufficiently attractive to elicit a private or corporate donation if their budget cannot be stretched? But in return, there would be the reasonable expectation that the significance of the work would be recognised through some form of exhibition and publication. Myers, I know, has sounded out the Auckland War Memorial Museum to gauge their interest in his NZ work but the Museum, so far has been less enthusiastic than one would imagine, so the eventual fate of it is unknown unless another archive shows serious interest.

Such also is the situation for the life’s work of many fine photographers in New Zealand. As discussed, there are many reasons why our collecting institutions, while increasingly fussy, are far less proactive than they should be. Rather than wait for photographers to get their act together and approach them, the better approach would be to make lists of those most likely to have significant work at risk. As public servants they need to remember that any careless lack of interest, such as not answering letters or following up enquiries, risks the loss of good will needed to start the complex job of acquiring work in the first place. When those responsible for our pictorial heritage drag their feet, or don’t explain why the process could take considerable time, the concomitant result is to risk the loss of many uniquely significant bodies of work.

Acknowledgements

This is to acknowledge with thanks the generous help of many people in contributing to this investigation through their professional work in this specialist field of pictorial heritage within the social history and art spheres and for sharing their experiences and concerns here. They include Natalie Marshall and Matt Steindl at the Alexander Turnbull Library; Athol McCredie from The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa, Ron Brownson and Caroline McBride from the Auckland Art Gallery; Shaun Higgins at the Auckland War Memorial Museum, and Keith Giles at Auckland Libraries, in the North Island. And in the South Island, Sarah Murray and Jill Haley at the Canterbury Museum; and Ken Hall at the Christchurch Art Gallery. We are grateful to those institutions among them who have kindly allowed us to publish images of significant photographs already saved and treasured by them.

We are grateful also to feature the specific contributions of Gael Newton, Roslyn Russell and Kylie Winkworth from Australia, and Caroline McBride from Auckland, who are all leaders in their fields. Thanks are due to Barry Myers, and Max Oettli for allowing their experiences to become case histories, along with those of the late Paul C Gilbert (supported by his sister Linda Gilbert and Rim publisher Haruhiko Sameshima), and that of Tom Hutchins whose remarkable legacy I have been documenting for 30 years because he didn’t.

Valuable exhibition installation views have been provided by Mark Beatty and Paul Chapman from the Turnbull Library and Auckland Art Gallery, respectively and both Sal Criscillo and Chris Bourke who kindly made photographs of ‘The Simple Image: The photography of Barry Clothier’ exhibition at the Turnbull for me to understand its content and form..

Some of the points I wanted to make, and reminders of the important technical and practical advances brought by digital copying, had to be made with historical examples and comparisons from public or private collections. But generally, I have tried to illustrate different points with digital copies of a variety of images that I think should be preserved for posterity but have not been acquired for any public collection to the best of my knowledge and are therefore a part of the endangered species of analogue photographs at the heart of my concern. It is impossible for me to represent anything near to a full spectrum of what could be discovered either in quantity or quality simply because no audit of potential collections has been done to identify the unique content of hundreds of presently unknown collections of significant analogue work. Some of the illustrations I have added are placed to inform and challenge institutional policies which specifically exclude certain subject matter, even though I know of many cases where wisdom has prevailed to save works that otherwise would fall between categories and be lost. Guidelines are necessary, but always there can be exceptions to the rule.

More than 30 individual photographers have kindly permitted us to include one or more of their photographs in this survey, for which we are grateful, but at the same time aware that many of them belong in the category of significant photographers that no heritage department or collecting institute has approached them about the possibility of inspecting their body of work or potential custody of it for posterity when they can no longer care for their work themselves – the central theme of this blog series.

Thanks are thus due to: Peter Black, Kevin Capon, Tony Carter, David Cook, Sal Criscillo, Brian Donovan, Reg Feuz, Bernie Harfleet, Martin Hill, Murray Hedwig, King Tong Ho, Robyn Hoonhout, Megan Jenkinson, family of Sale Jessop, John Johns’ family, Hanne Johnsen, Ian Macdonald, Mary Macpherson, John Miller, Mac Miller, Barry Myers, Anne Noble, Max Oettli, Craig Potton, Doc Ross, Tom Shanahan’s family, Frank Schwere, Jenny Tomlin, Tim J Veling, Ans Westra, Wayne Wilson-Wong, and Diana Wong.

For editorial help I am most grateful to Haru Sameshima at the middle stage of restructuring this series, even when I did not always act on his advice; and also to PhotoForum Web Manager Geoff Short for tidying up my messy attempt to create a series of blogs of relevance to photographers and picture specialists so they can see shared issues from each other’s point of view. The need now is for photographers and archivists to work together to ensure that photographers collections are not destroyed due to ignorance or an acute shortage of specialist staff and facilities.

Currently, despite plenty of formal policies and well thought out expressions of intentions for the preservation of our visual heritage, it is disturbing to detect so little evidence, despite the warning signs, that the official guardians of New Zealand’s visual heritage have turned a blind eye to what can be argued was one of the most active and relevant movements for the photographic recording a period of great change in New Zealand society due to a pivot away from Great Britain toward the larger world. To neglect the bodies of work by hundreds of dedicated practitioners of analogue photography from the latter half of the 20th Century, for whatever reasons, as seems to be the case, heralds a monumental disaster and mockery of our visual heritage aspirations. But with serious attention and collective action it is, hopefully, not too late to avoid that disaster which would once again see New Zealand’s photo treasures heading for the tip.

-John B Turner, Consulting Editor, PhotoForum Inc.

About the editor

John B Turner was born in Porirua, New Zealand in 1943, and became an enthusiastic amateur photographer who participated in the camera club movement as a teenager. In Wellington, he worked first as a compositor at the Government Printing Office, then as a news and commercial photographer at South Pacific Photos. He was briefly a photographic printer for The Dominion newspaper, a mural printer for the National Publicity Studios, and later the photographer at the Dominion Museum (now part of The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) during the 1960s. Before joining Tom Hutchins, the pioneering academic in photography and film, as a lecturer in photography at the Elam School of Fine Arts, University of Auckland in 1971 Turner had written widely about the medium and co-curated the exhibitions ‘Looking & Seeing’ (1968), ‘Maori in Focus’(1970). He also curated the landmark 'Nineteenth Century New Zealand Photographs’ exhibition of 1970 while working in Wellington.

From Auckland he curated 'Baigent, Collins, Fields: three New Zealand photographers’ (1973), and initiated 'The Active Eye' survey of contemporary NZ photography in 1975. The founding editor of PhotoForum magazine 1974, he has written widely on many aspects of photography for local and international publications. He was a former director of Photoforum Inc., and is currently a consulting editor and contributor. He studied the history of photography with Van Deren Coke and Bill Jay, at Arizona State University, Tempe, U.S.A., in 1991, and was co-author with William Main of the anthology New Zealand Photography from the 1840s to the Present (1993). He edited and designed Ink & Silver (1995), and also Eric Lee Johnson: Artist with a Camera (1999). He was a member of the Global Nominations Panel for the Prix Pictet Prize, London, and has lived in Beijing, China since 2012, where he continues to curate shows and write about aspects of historical and contemporary photography in New Zealand and China. In 2016 with Phoebe H Li, he co-curated a survey exhibition for Beijing’s Overseas Chinese History Museum of China, titled ‘Recollections of a Distant Shore: New Zealand Chinese in Historical Images’, and co-edited and supervised the production of a bilingual book of the same title. That exhibition was later reconfigured as a year-long feature by the Auckland War Memorial Museum. Turner curated the first exhibition of Robert (Tom) Hutchins’s work for the 2016 Pingyao International Festival, and published the catalogue Tom Hutchins Seen in China 1956, with the Chinese translation and production assistance of filmmaker Han Niu. He has since placed Hutchins’s China photographs with the VCG (Visual China Group) and Getty Pictures agencies. Hutchins’ work has gained international acclaim and was featured along with Brian Brake in the Chinese language anthology China through the lens of foreign photographers (2020) and is now available in English.

Turner first exhibited his work outside of the NZ camera club and NZ Professional Photographers’ Association circles (for whose magazines he also wrote) in 1965 with a joint show with Barry Clothier at Artides Gallery, Wellington, and in the 1980s had two solo exhibitions at William Main’s Exposures Gallery in the capital city. He features in several capacities in Nina Seja’s Photoforum at 40: Counterculture, Clusters, and Debate in New Zealand (2014). In 2019 his work was included along with seven peers in ‘The New Photography’ exhibition and book about New Zealand’s first-generation contemporary photographers of the 1960s and 1970s, curated by Athol McCredie for The Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa.

His website 'Time Exposure' is at www.jbt.photoshelter.com and you can contact him at johnbturner2009@gmail.com

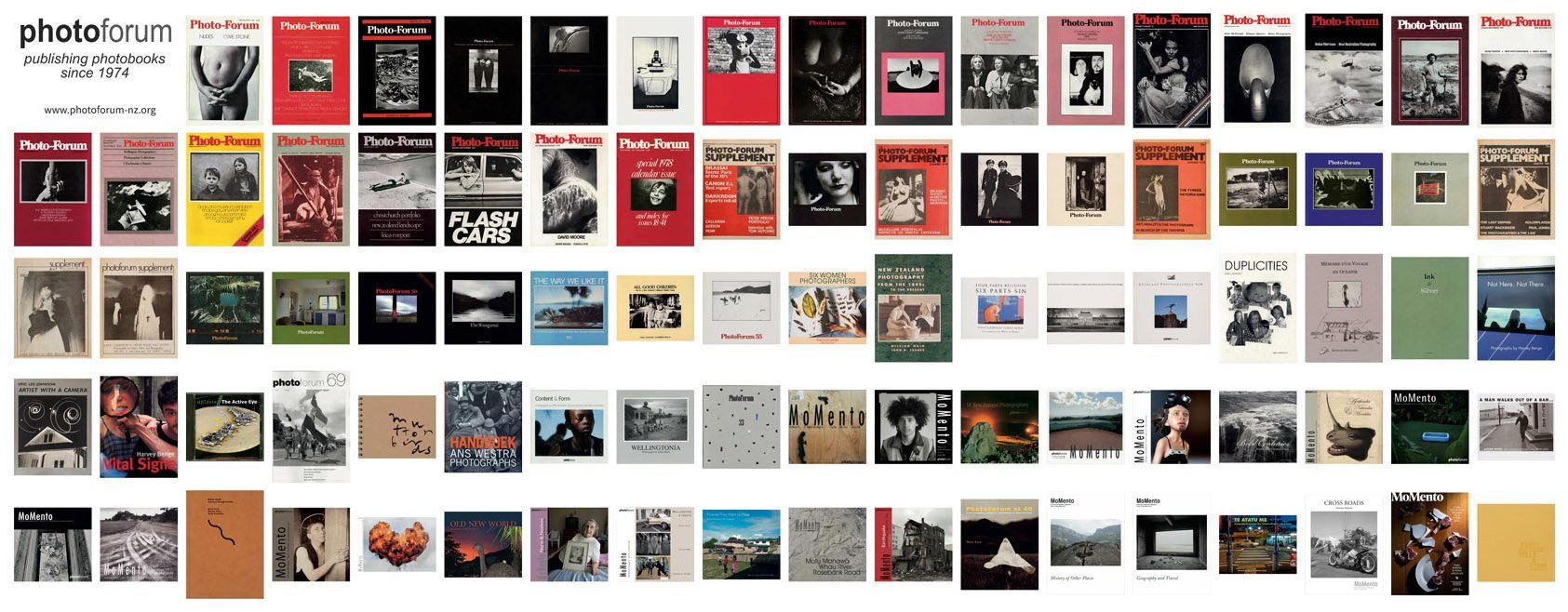

About PhotoForum

PhotoForum Inc. is a New Zealand non-profit incorporated society dedicated to the promotion of photography as a means of communication and expression. We maintain a book publication programme, and organise occasional exhibitions, workshops and lectures, and publish independent critical writing, essays, portfolios, news and archival material on this website - PhotoForum Online.

PhotoForum activities are funded by member subscriptions, individual supporter donations and our major sponsors. If you would like to join PhotoForum and receive the subscriber publications and other benefits, go to the Join page. By joining PhotoForum you also support the broader promotion and discussion of New Zealand photography that we have actively pursued since 1974.

If you wish to support the editorial costs of PhotoForum Online, you can become a Press Patron Supporter.

For more on the history of PhotoForum see here.

The opinions expressed by the authors and editor of this report are not necessarily those of PhotoForum Inc.

CONTACT US:

photoforumnz@gmail.com

PhotoForum Inc, PO Box 5657, Victoria Street West, Auckland 1142, New Zealand

Directors: David Cowlard & Yvonne Shaw

Consulting Editor: John B Turner: johnbturner2009@gmail.com

We need your help to continue providing a year-round programme of online reviews, interviews, portfolios, videos and listings that is free for everyone to access. We’d also like to dream bigger with the services we offer to photographers and the visual arts.

We’ve partnered with Press Patron to give readers the opportunity to support PhotoForum Online.

Every donation helps.